London has been very proactive in trying to attract, support, and retain immigrants.

Kareem El-Assal, London Free Press, March 7, 2020

On March 2, 1793, Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe chose the forks of the Thames River as the site for the capital of Upper Canada. It was not to be, and no newcomers settled at the site for over 30 years.

In 1826 that changed. Officials decided London would host the new courthouse and jail. As the administrative centre for the London District, the community grew fast. London soon became the commercial, military, and industrial hub of the surrounding region. It continues to attract new residents today.

Here, we share stories of the people who have made London home and the policies and processes that shaped their experiences.

Explore the time periods that shaped London…

Early 19th Century

Late 19th Century to the First World War

20th Century

Early 19th

Century

At first many immigrants to London and the surrounding region came from the United States. Later the majority came from Great Britain.

After the British Constitution Act established Upper Canada in 1791, more and more newcomers began to settle in the western part of the area. In 1826, they began to settle in London.

At first, many of these settlers came from the United States and other parts of British North America. With the end of the War of 1812 in 1815, however, immigration from Great Britain skyrocketed. Rural poverty and urban unemployment drove thousands to seek new opportunities in Canada.

London grew from a village to a town to a city in a matter of 30 years.

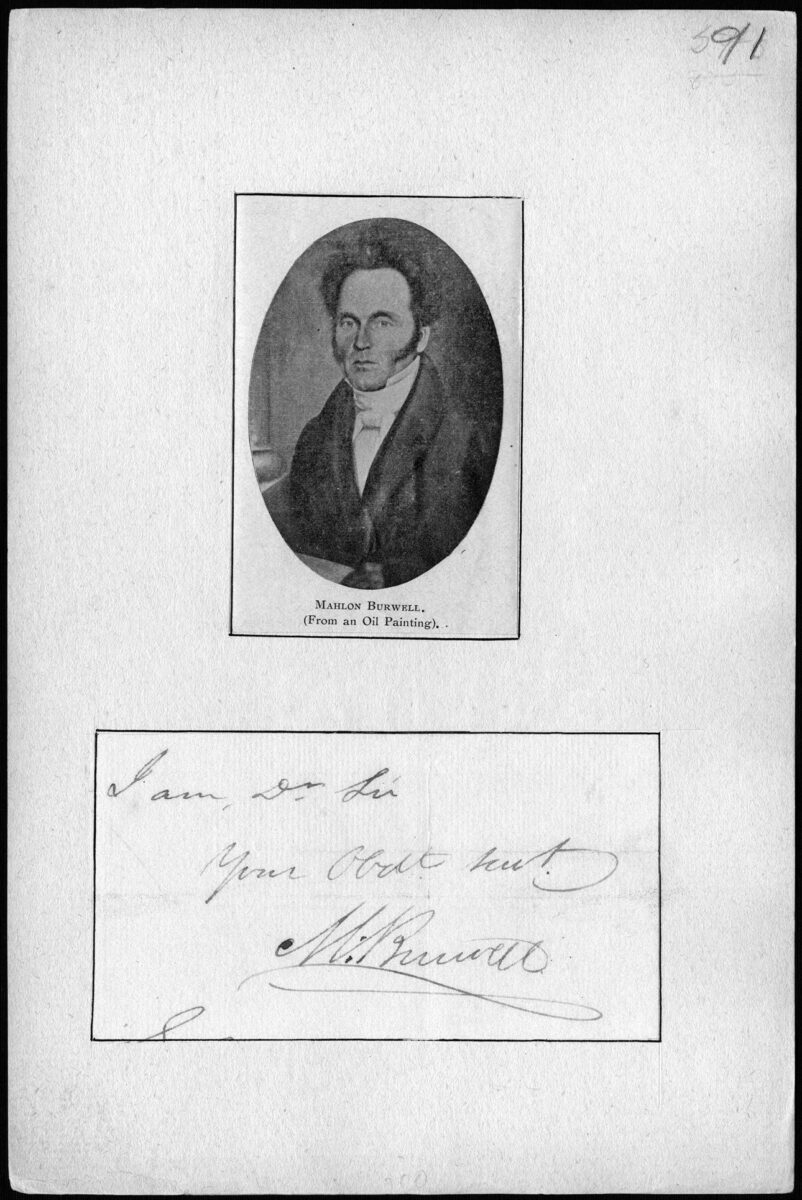

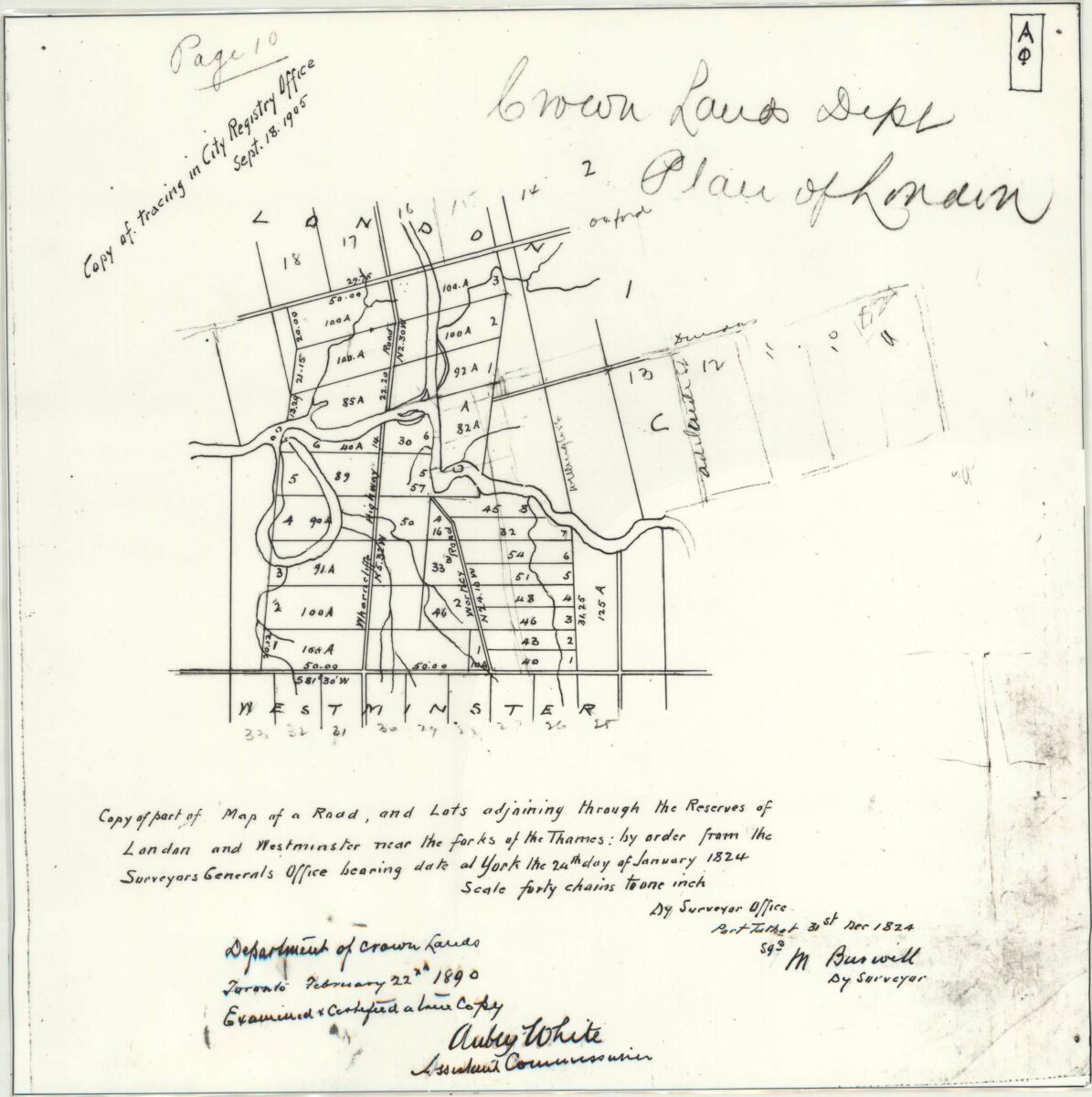

Laying out London

American-born land surveyor Mahlon Burwell, pictured to the right, used this surveyor’s reel in the 1820s. Perhaps he used it to draw this 1826 map (far right) of the village that would become London. Working for the provincial government, Burwell also laid out roads and townships across southwestern Ontario.

2015.026.023

New Administrative Centre

This wooden building was London’s temporary courthouse and jail from 1826 to 1829. It replaced the London District courthouse and jail in Vittoria, Upper Canada, damaged by fire in 1825. Because newcomers had moved westward away from Vittoria, Simcoe’s proposed village of London became the new administrative centre for the district.

Bustle and Activity

Workers completed London’s stucco-covered brick courthouse in 1829. British army surgeon George Russell Dartnell’s watercolour depicts it in 1841. The building of this structure and the activity that occurred within its walls attracted many new residents and businesses to London.

London’s First White Newcomer

In 1937, a stone grave marker replaced this wooden one at Peter McGregor’s final resting place. McGregor is considered London’s first white newcomer. Born in Scotland in 1793, he arrived in the London District in 1825. He worked for surveyor Mahlon Burwell, opened London’s first tavern in 1826, and was the community’s first jailer.

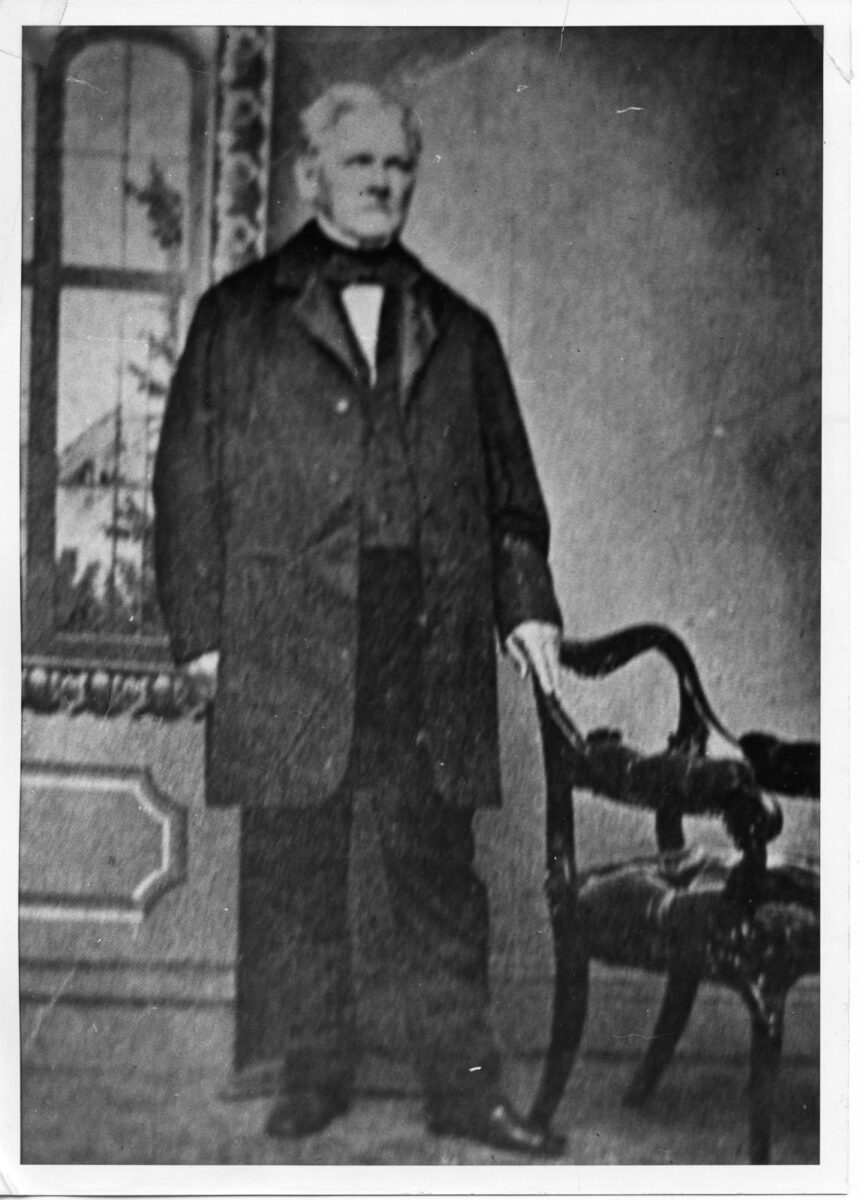

An Entrepreneur

American-born George Jervis Goodhue was one among many Americans to leave the United States to settle in Upper Canada after the War of 1812 (1812-1814). First living in Westminster Township, Goodhue moved to London in 1826 when it became the district capital. He established a prosperous business on the courthouse square. Although some worried Americans would bring their republican attitudes to British North America, government policies classed them as desirable immigrants.

Tolpuddle Martyrs

John Standfield made this box in 1836 to carry his belongings back to England from Australia. Two years earlier in 1834, he and five other men, the Tolpuddle Martyrs, had been transported to Australia for banding together to protest agricultural labour wage cuts. Mass protests across Great Britain led to their pardon. John and four others later immigrated to Canada and settled in the London area. The men were part of a surge in immigration from Great Britain that impacted London and other parts of British North America in the 1830s.

Slowing Immigration

John Weyman Price and his wife, Elizabeth, immigrated to London from England in 1855. John used the lantern in his job as an engineer with the Great Western Railway, later the Grand Trunk Railway. Because of the Crimean War (1853-1856), immigration rates dropped in the mid-1850s. Great Britain needed men for its army and male and female industrial and agricultural workers to fuel the war effort.

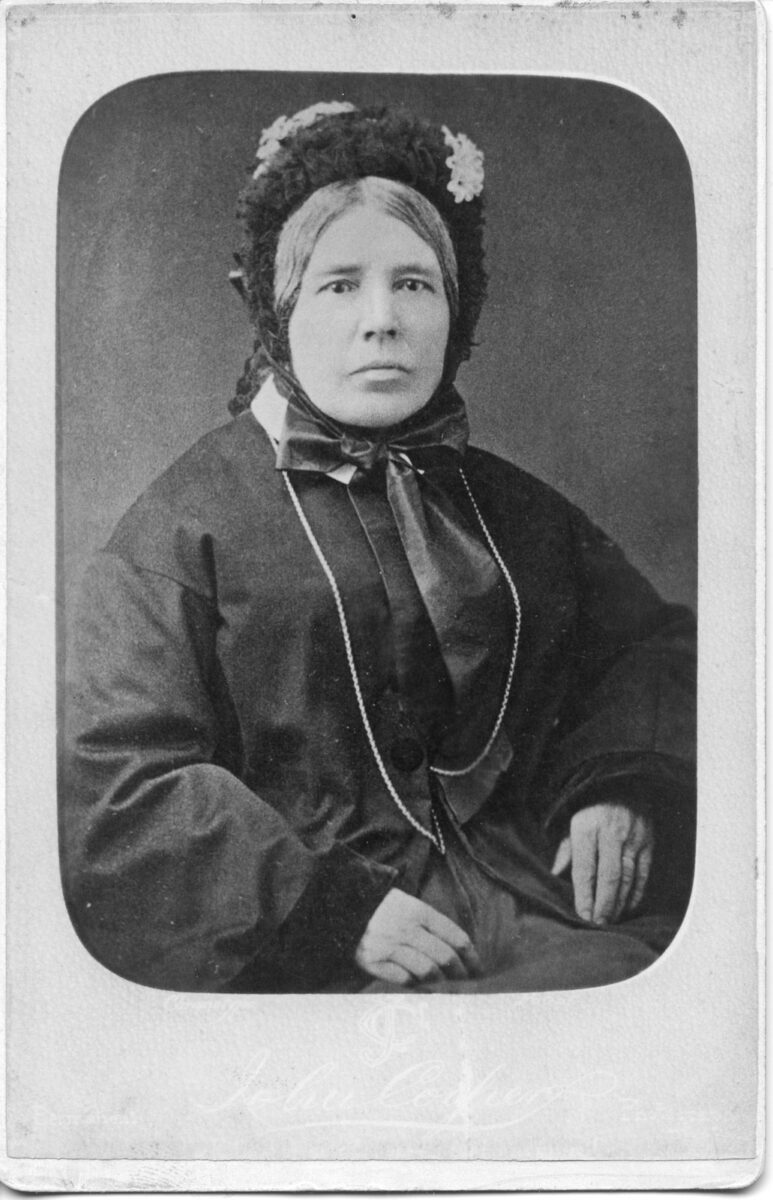

The Irish

Anne McCormick Porte (far right) and her family arrived in London in 1829 from County Down, Ireland. Fourteen-year-old Ann Marshall (right) and her family left Ireland and settled in London in 1834. Ann brought the doll below, Fanny, with her. Between 1847 and 1854, hundreds of thousands more Irish arrived in British North America, some settling in London. They were fleeing the potato famine that devastated the country.

Escaping Slavery

Alfred T. Jones escaped his white enslaver in Kentucky in 1833 and arrived in London the same year. When Benjamin Drew interviewed him in the 1850s, Jones owned an apothecary shop on Ridout Street. He noted about his compatriots: “There are coloured people employed in this city . . . many are succeeding well[.]” Those who escaped slavery made London home because it was close enough to reach from the American border. It was also far enough away to avoid recapture.

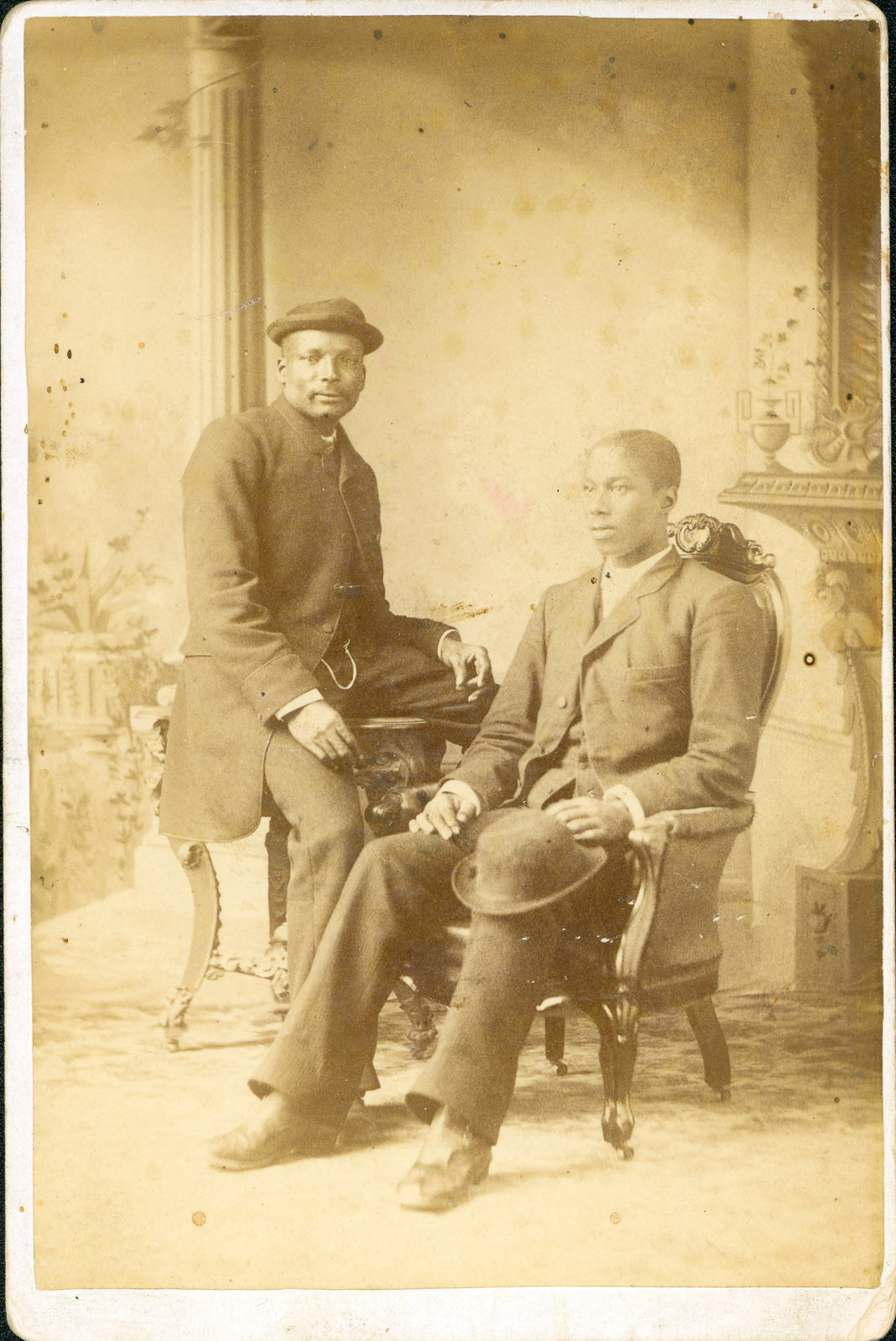

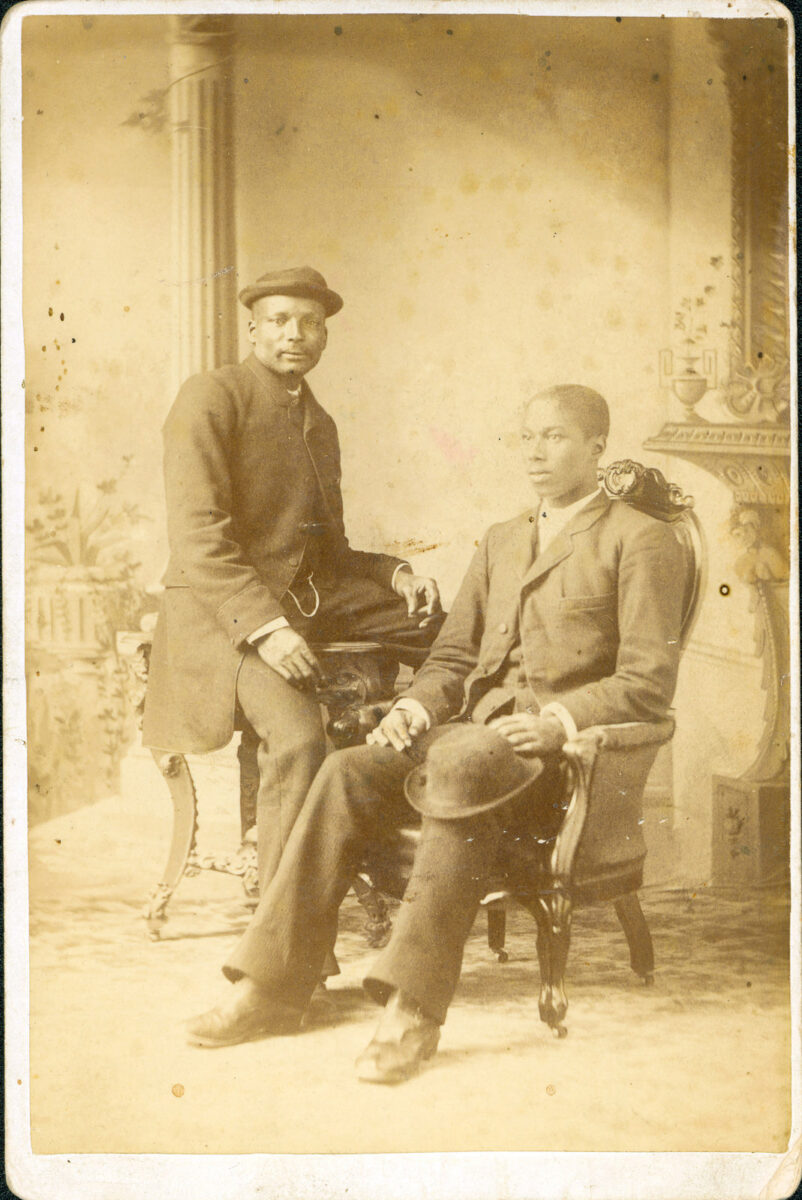

London’s Black Population

London photographer John Cooper’s cabinet card depicts two unnamed Black men in the late 19th century. In 1861, census figures reveal almost 600 Black people lived in London and the surrounding area. That number fell to around 350 in 1901. This decline reflected the impact of the late 1850s recession. It also resulted from growing industrialization, urbanization, and racism, which reduced opportunities for Black people in London. Not only did some Black people leave but also officials stopped potential Black American immigrants at the border. From the late 19th century through to 1967, Canadian officials believed they could not adapt to Canada’s climate.

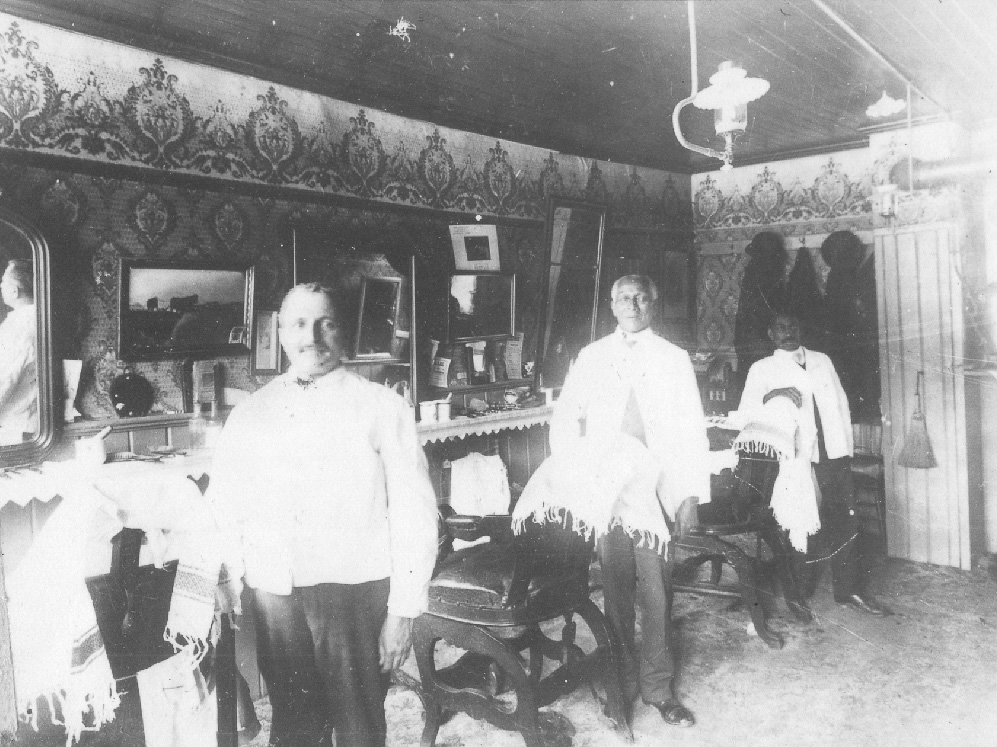

Shadrack “Shack” Martin

Here London barber “Shack” Martin (middle) is at work in George Taylor’s King Street barber shop around 1908. Martin had immigrated to London in 1854, one of hundreds of African Americans to leave the United States following the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. This act required authorities to return people escaping enslavement to their enslavers. Slave catchers also captured free Black people, selling them into slavery.

Late 19th Century to

the First World War

After 1867, London benefitted from the new federal government’s efforts to promote immigration to populate the newly formed dominion.

After the passage of the British North America Act on July 1, 1867, Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald recognized the need to populate the country.

Government officials gave preference to immigrants who were farmers with capital, agricultural labourers, or female domestics. And they came, in order of preference, from Great Britain, the United States, and Northern Europe. And yet many others came as well.

Although Macdonald was focused on populating Canada’s west, new immigrants settled across the country, including in London.

London grew from a village to a town to a city in a matter of 30 years.

Chinese Immigration

Overcoming Adversity

Here, Lem Wong sits with his wife, Toye, and their eight children in 1961. The children grew up doing the same things as other London youth. They went to school, attended church services, and threw themselves into local sports. They felt a sense of belonging. But they experienced racism too. Visible minorities in what was a white, conservative community were not permitted to forget they were different.

Wong had immigrated to Canada from China in 1896. As the federal Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 demanded, he paid a head tax of $50. After working in laundries across the country including in London, he opened his café in 1914. In 1911, he paid a head tax that had risen to $500 so that his wife, Toye Chin, could join him. Their five-year-old son, Victor, came with her.

Hop Sing Laundry

1961.127.027

Hop Sing operated his laundry on Clarence Street in the 1920s. He was one of several Chinese men operating laundries in London in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. With the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in the mid-1880s, many Chinese workers headed east. The racist attitudes of employers and trade unions drove many to work as domestic servants, laundrymen, or restaurant workers.

1986.029.002

Searching for Opportunity

Jane Berry Manness (left), her husband, Frederick, and their five children emigrated from Jersey in 1872. They were among more than 4,000 Jersey residents, just over seven per cent of the population, to leave the island between 1871 and 1881, after its economy declined.

1993.036.016

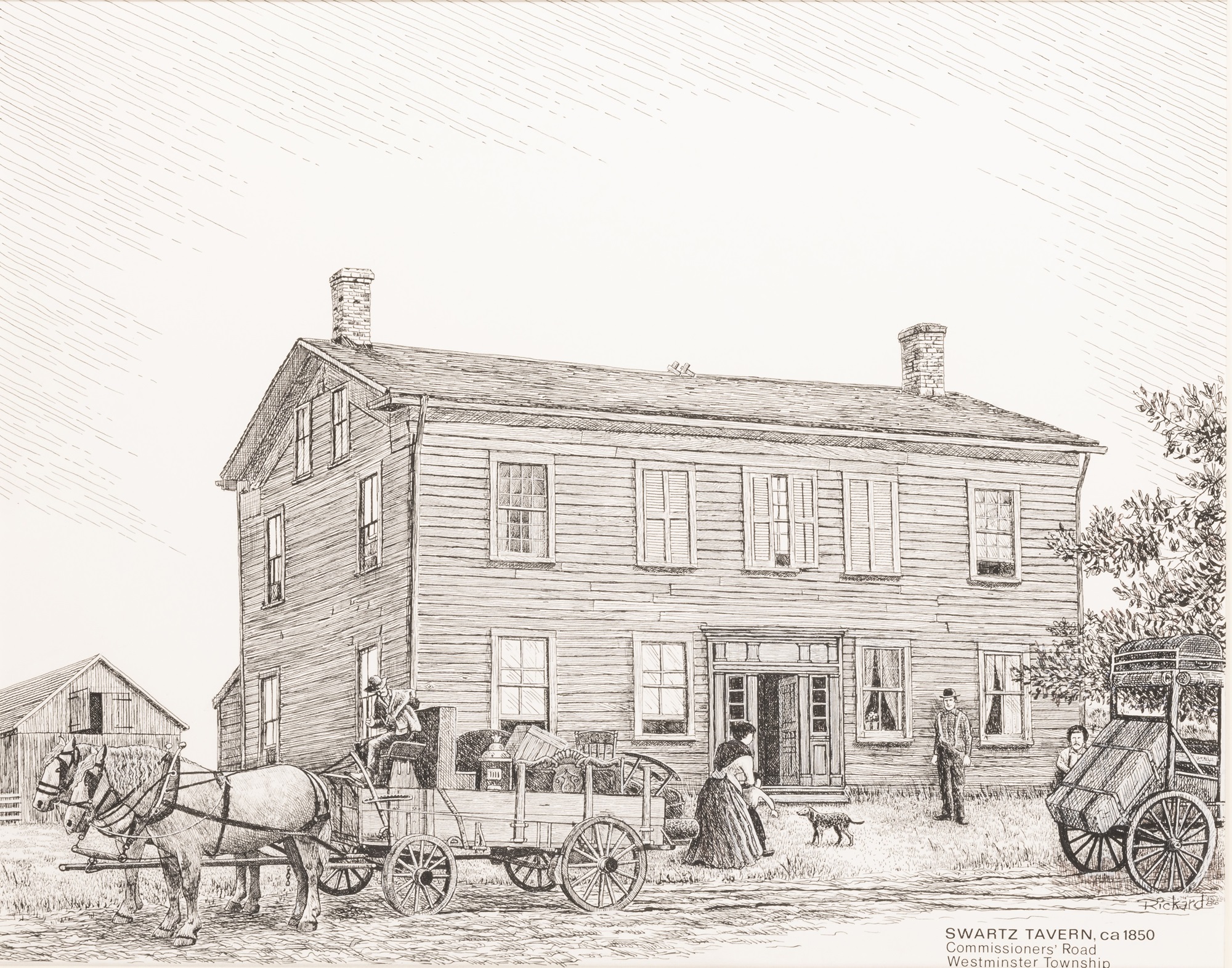

A Home for Child Immigrants

Built as Swartz Tavern around 1822, this building became the Guthrie House from 1874. English philanthropist Dr. John Middlemore operated it as a receiving home for impoverished British children he chose to place with Canadian families. More than 2,000 came to London by the time the Guthrie House closed around 1900. Although criticized, child emigration schemes like Middlemore’s saw some 100,000 British “home children” come to Canada by 1939 when the programs officially ended.

Jewish Immigration to London

William Leff opened his scrap and salvage business in London in 1898. It endured as a family business until 1972. Leff, with his parents and siblings had immigrated to London from Russia in the early 1890s. They fled growing anti-Semitism in their homeland, which fueled violence and caused economic hardship. They joined London’s small, but growing, Jewish community.

In 1920, William Leff built this three-story facility at 555 Bathurst Street for his growing business. Leff often hired new Jewish immigrants, helping them to begin new lives. Ensuring his workers could respect the Jewish Sabbath on Saturday caused Leff trouble. In 1909 he was fined $10 and costs (around $300 today) when two of his employees worked on Sunday. This violated the 1906 Lord’s Day Act, only repealed in 1985.

Click on the objects to learn more…

20th Century

World events, and their impact on Canada and Canadians, determined the numbers of immigrants to come to London in the 20th century. It also dictated the countries from which those immigrants came.

In the first half of the 20th century, immigration to Canada plummeted because of the First World War and then the Great Depression. The federal government implemented strict measures to limit the number of people who could enter Canada.

After the Second World War, immigration took off. Many came from war-affected countries. The federal government also began to dismantle its racist immigration infrastructure. For example, in 1947, it repealed the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act.

Prepared to Work

British immigrant Charles Wray brought these tools with him when he came to London in 1906 in search of a better life. He was part of a surge in British immigration to Canada at that time. Minister of the Interior Clifford Sifton had launched an aggressive recruitment campaign in Great Britain. Within a decade, after the First World War (1914-1918) began, immigration slowed to a trickle.

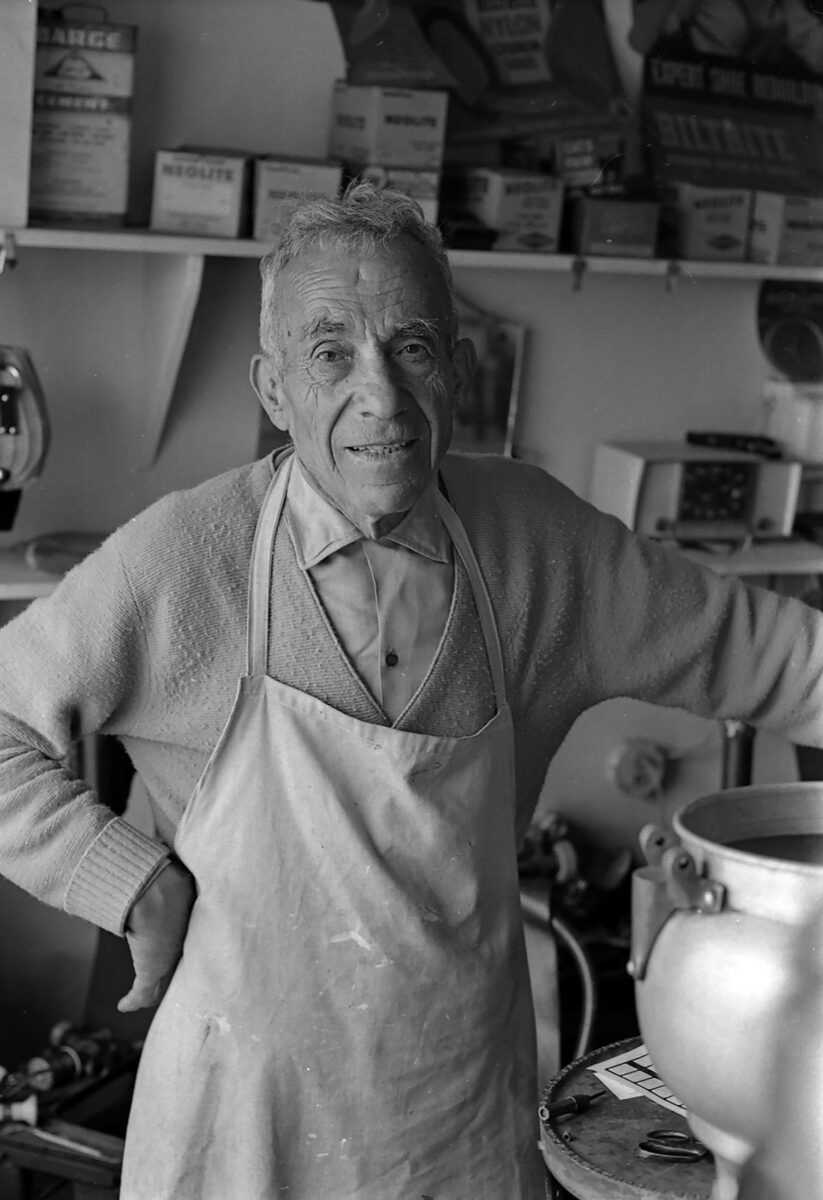

Family Connections

Greek immigrant Bill Agnos, pictured here in 1972, emigrated to London from Greece in 1927. His father-in-law, James Liabotis, already in London, encouraged him to come. Since Greece was struggling with economic and political instability, there were few opportunities there. After working for his father-in-law, Agnos opened the Capital Shoe Repair and Hat Cleaners in 1934. It was a fixture in London for over 40 years.