1959.042.005

Early London included farms, stores, and small industries that served a growing local market

As the population grew and transportation networks improved, London’s manufacturing sector took off. Entrepreneurs established a wide range of industries in which workers produced goods for expanding local, regional, national, and international markets.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, these industries responded to changing technology and markets. Some even continue to operate today.

Explore the industries that helped make London the thriving city it is today…

The McCormick Manufacturing

Company Limited

The Little Lord Fauntleroy trademark … represents quality and stands for the highest achievement in the art of biscuit making.

Canadian Grocer, March 1918

The McCormick Manufacturing Company produced biscuits, crackers, and candies in London for almost 150 years.

Thomas McCormick opened the Dominion Steam Confectionary and Biscuit Works in 1858.

By 1879, the business became the McCormick Manufacturing Company Limited. The company flourished, serving first the region, and later establishing branches across the country.

In 1926, McCormick’s purchased competitor, D. S. Perrin and Company. Together, they became the Canada Biscuit Company. After changing hands multiple times, the business closed in 2006.

McCormick’s Second Factory

In 1872, Thomas McCormick built the factory depicted on this crate. Located on the southeast corner of Dundas and Wellington streets, this factory replaced a smaller one that stood on Clarence. As the black smoke coming out of the chimney illustrates, coal fires produced the steam that powered the works.

Innovations in Packaging

In the 1880s, Thomas McCormick implemented unit packaging, like this tin, for retail sales. Before, manufacturers had shipped crackers to retailers in bulk using barrels. To create brand recognition, in the 1890s McCormick adopted a recognizable logo: Little Lord Fauntleroy, a character author Frances Hodgson Burnett introduced in 1885.

The “Sunshine Palace”

In 1913, the McCormick Manufacturing Company, Limited built a new factory in East London, drawn by tax breaks London’s city council had offered. Local architects, Watt and Blackwell, designed it. Nicknamed the “Sunshine Palace,” the building contained 45,000 feet of glass and was celebrated as the most sanitary candy factory in North America. Now a heritage structure, plans are underway to turn the building into apartments, offices, and retail space.

Women Workers

In this 1915 photograph, women work at a wrapping machine in the “Sunshine Palace.” Thomas McCormick, Jr., had considered the needs of his female workers when designing the factory. Competition for women workers at the time meant that employers who provided the most attractive workplaces would attract and retain the best workers. At the McCormick factory, women enjoyed showers, a library, break rooms, a gymnasium, and more.

Employee Cafeteria

McCormick workers, both women and men, received one cent tokens like this to redeem at the company cafeteria. Here, employees could purchase inexpensive meals. The cafeteria was another of the amenities included in the “Sunshine Palace” to promote employee loyalty and satisfaction. The company’s earlier factory had also included separate dining rooms for men and women.

2024.001.028

Link Between Businesses

London’s Somerville Limited, a company that produced paper boxes among other products, manufactured this McCormick’s biscuit box. In fact, McCormick’s was C. R. Somerville’s first customer.

Kellogg Company

of Canada Limited

Kellogg’s Toasted Corn Flakes is boon to the public in general.

London Ontario, 1914, 1914

Kellogg’s began in London in the early 20th century. Changing consumer tastes among other factors led the factory to close in 2014.

In 1906, a group of London businessmen established the Battle Creek Toasted Cornflake Company on Grey Street.

The company grew fast, and in 1914, relocated to a new, larger factory in east London. Renamed the Kellogg Company of Canada in 1924, the business was a fixture in London until 2014.

Today the factory building, now called 100 Kellogg Lane, has been converted into an entertainment destination.

Life Chips

The short-lived Battle Creek Health Food Company transported its cereal, Life Chips, in this crate. This predecessor of the Battle Creek Toasted Cornflake Company opened in London in 1905 and closed by January 1906. Although the company advertised the health-giving properties of Life Chips and its other products, customers did not respond.

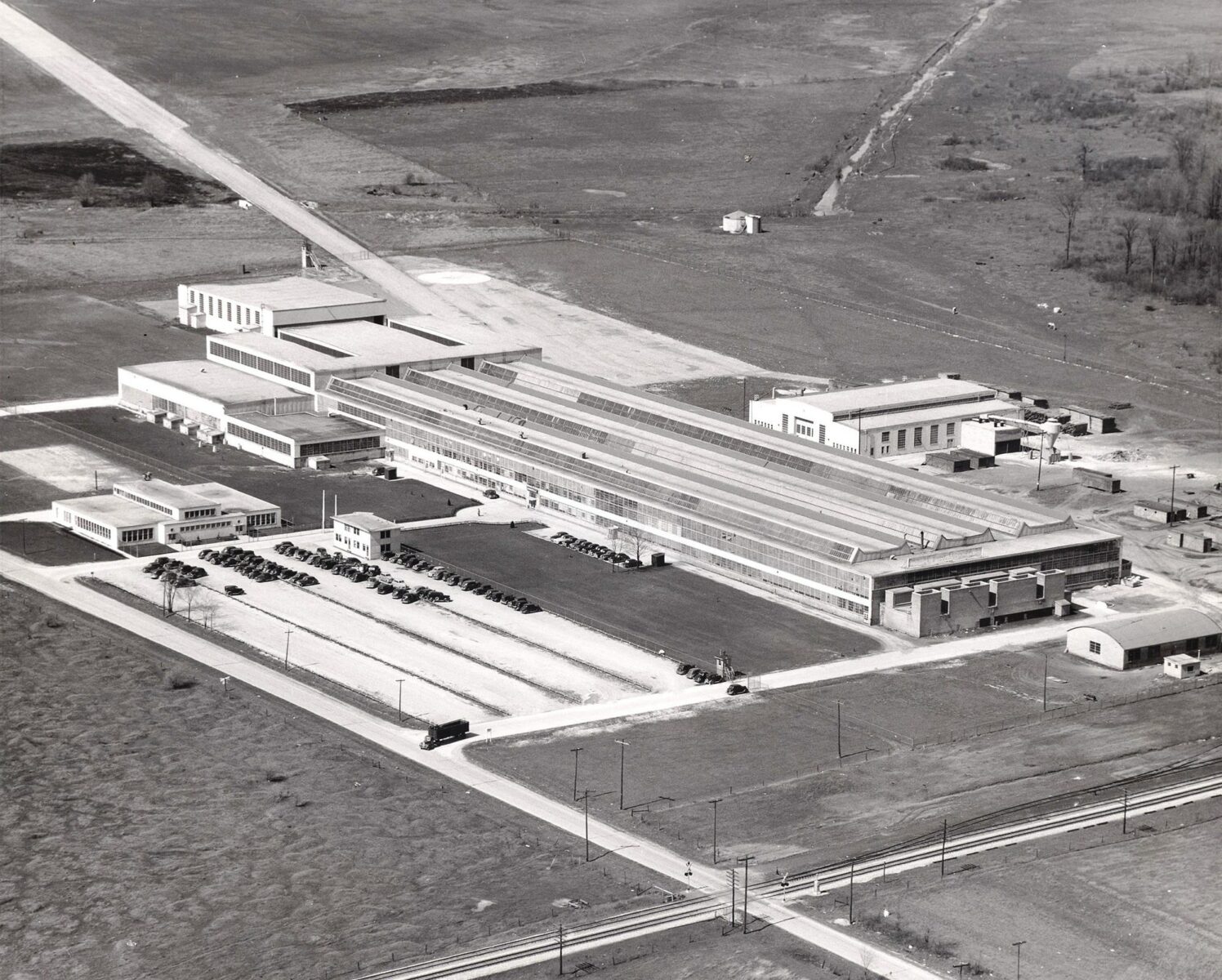

A New Home

London photographer, Arthur Gleason, captured this aerial view of the Dundas Street Kellogg plant in the 1930s. The company had relocated to this East London site in 1914. Hydroelectricity, introduced in London in 1910, powered the facility.

2004.020.139

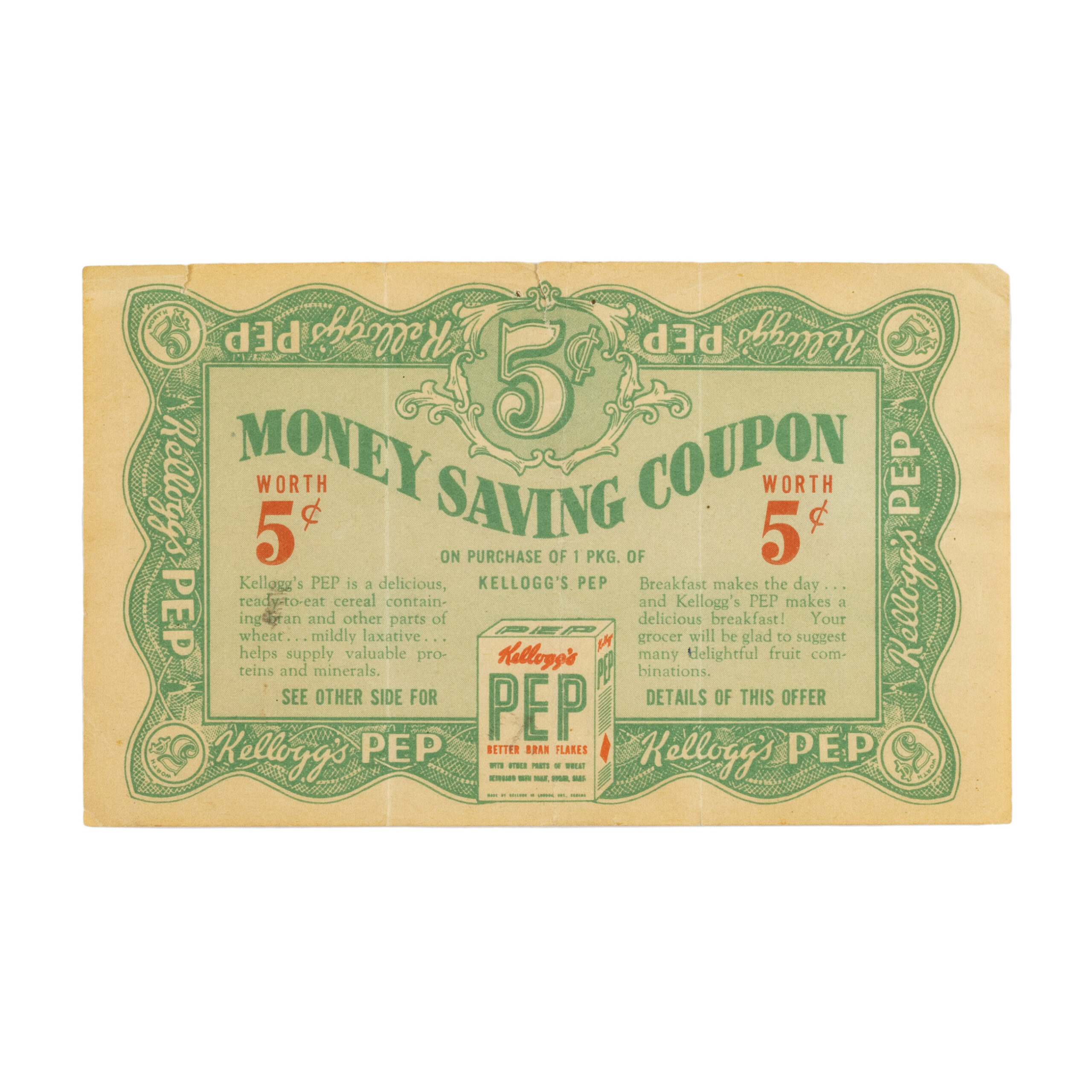

A Product for Every Taste

Over the years, Kellogg’s produced a range of products from Pep to Krumbles to Frosted Flakes. Over time, though, tastes changed. By 2013, when Kellogg’s announced it would close a year later, cereal sales had declined. Consumers preferred other breakfast foods.

Kellogg’s Leaves London

Kellogg’s employee, Steven Gordon, saved the box of Frosted Flakes (far right), one of the last to come off the production line on December 12, 2014. A company official explained that, along with slumping cereal sales, the aging London plant had become too expensive to maintain. Gordon was among 500 employees to lose their jobs.

Labatt’s Brewery

I have been considering this brewing affair for some time and I do think it would suit me better than anything else.

Letter from John Labatt to his wife, Eliza, 1847

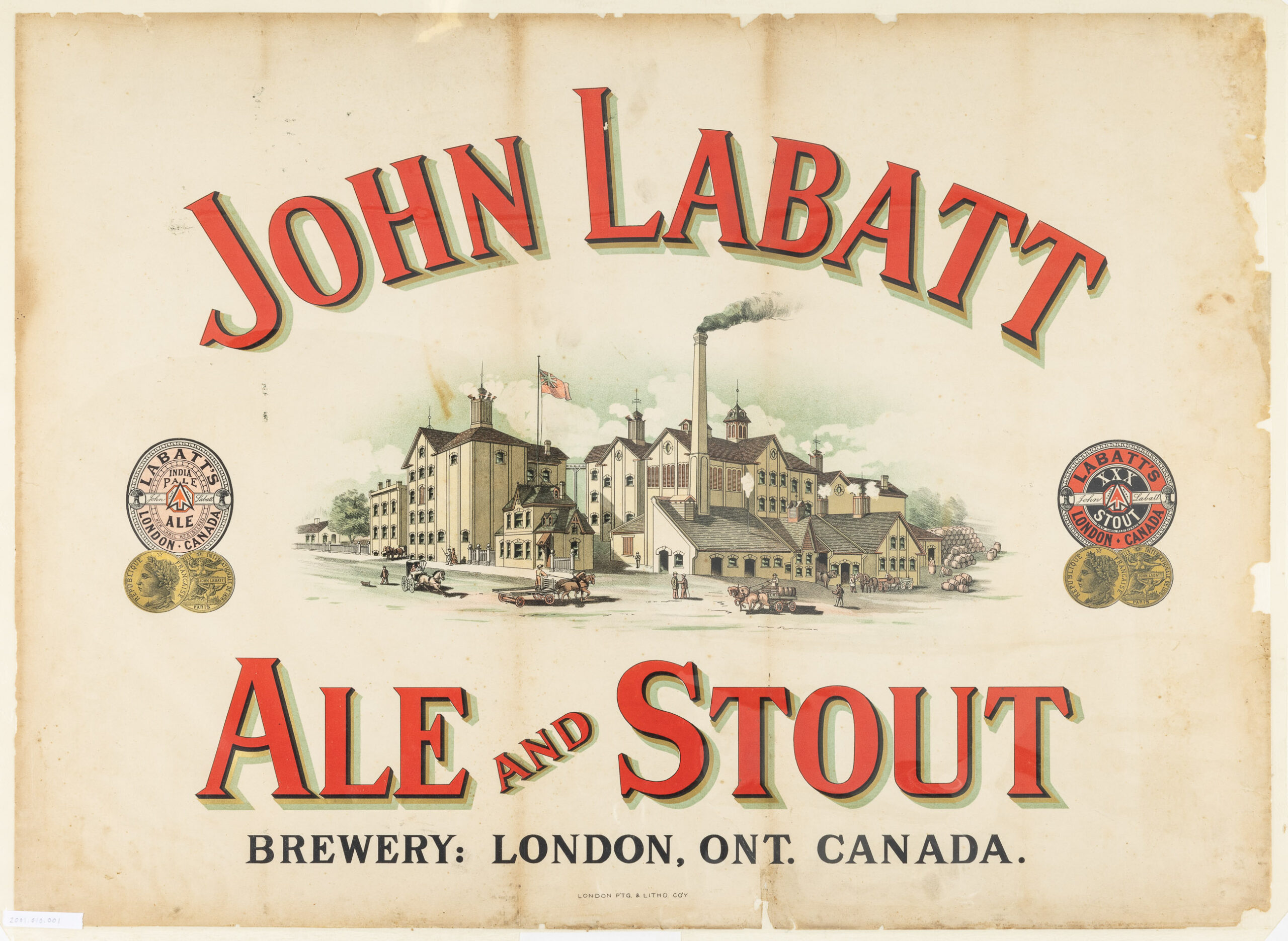

In 1847, John Kinder Labatt and his partner, Samuel Eccles, purchased the London Brewery. He became sole owner in 1853. Today, the brewery that bears his name is still operating in London.

Over its long history, Labatt survived Prohibition, fierce competition, and changing tastes.

It developed and introduced new products and product packaging to adjust to a shifting market. Over the decades, the company also evolved marketing strategies, like sports sponsorships, to attract consumers.

From the beginning, Labatt invested in the community. In London, it contributed funds for the restoration of historic landmarks and raised money to support local charities.

Although no longer Canadian-owned, Labatt’s still brews in London today.

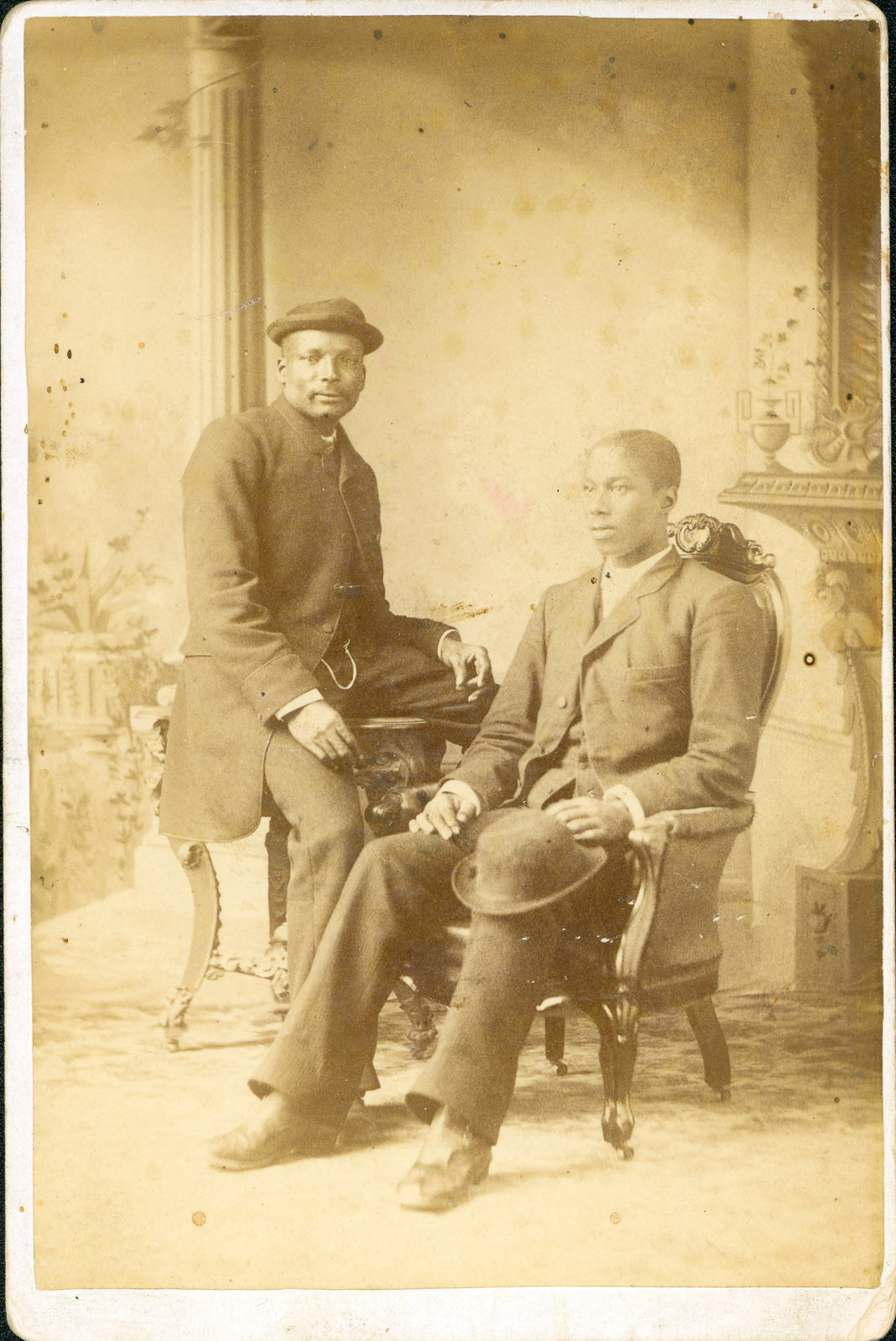

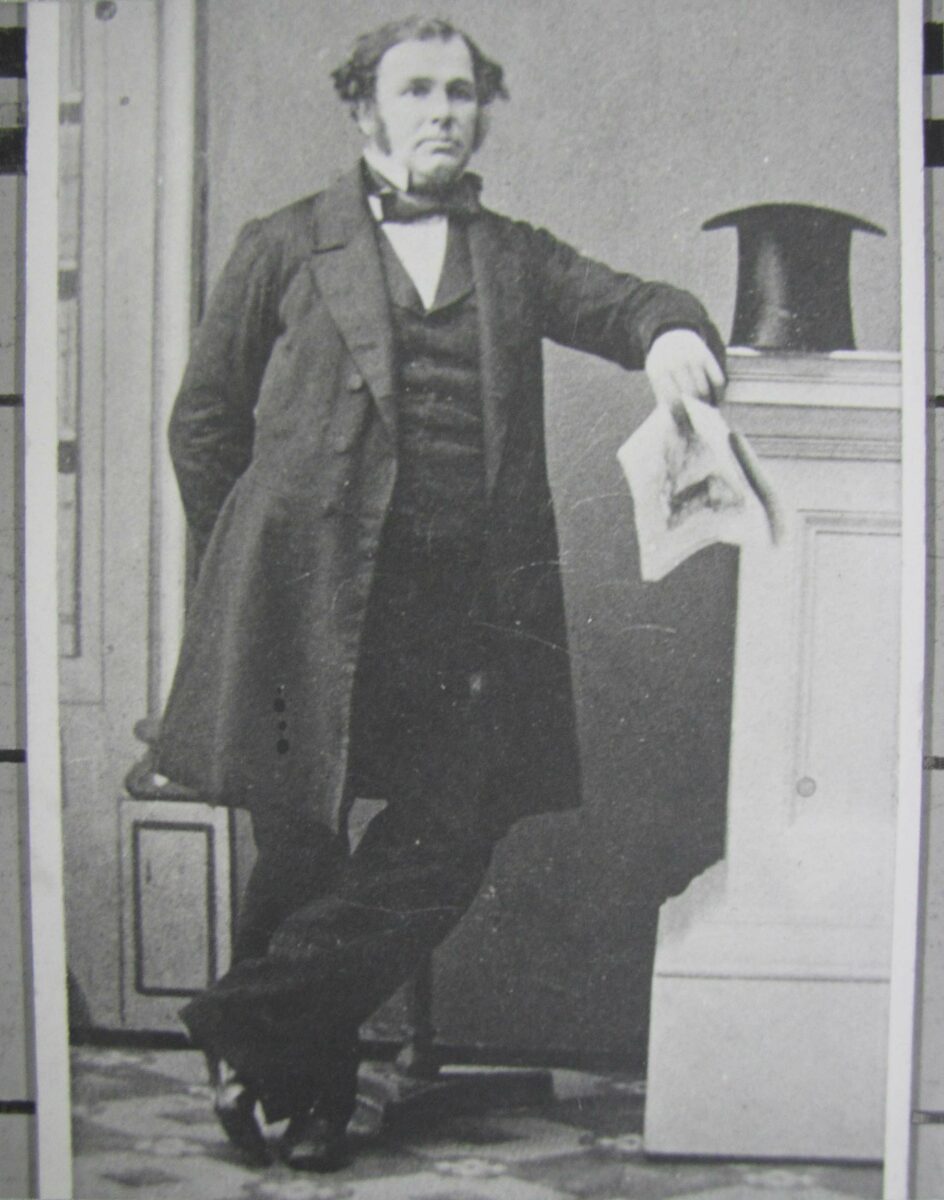

Balkwill Brewery

In 1828, John Balkwill established the London Brewery, depicted in this 1968 print. Balkwill produced 400 barrels of beer a year and sold much of it in his own tavern. Samuel Eccles purchased the operation from Balkwill and his brother-in-law, George Snell, in 1847. John Kinder Labatt, pictured here, at first Eccles’ partner, bought the brewery in 1853. He renamed it John Labatt’s Brewery.

2010.011.5437

2010.011.5444

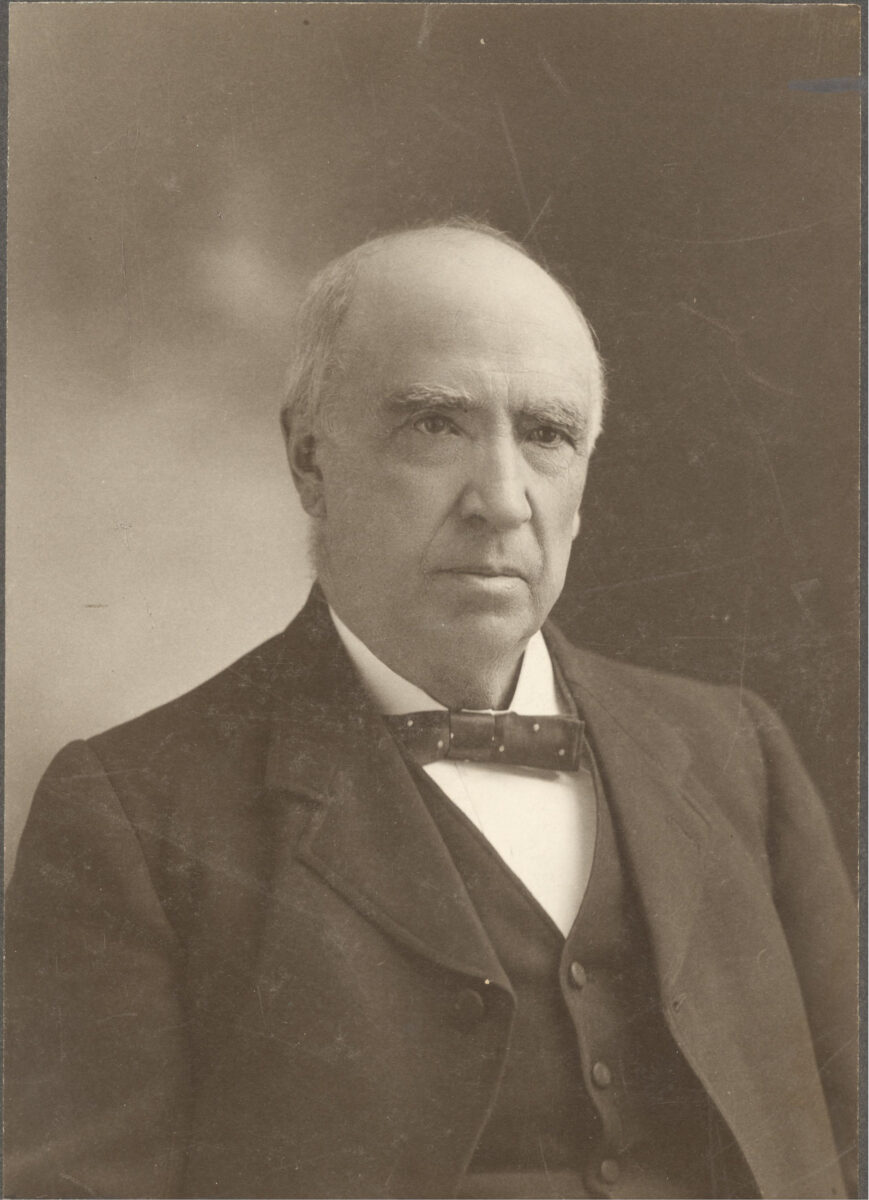

Prize-Winning Beer

The Labatt brewery won this medal at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1878. Afterwards, the company featured it on its beer bottle labels and advertising. By 1878, John Labatt junior, pictured here, had taken over the brewery. He entered the company’s products into many Canadian and international competitions. Winning medal after medal, the company gained fame and sales grew.

Temperance and Prohibition

In response to Ontario’s temperance movement, Labatt’s introduced a low-alcohol beer, Comet, in 1910. Later, during Prohibition (1916-1927), the company added two new low-alcohol beers: Cremo Lager and Old London Brew.

Surviving Prohibition

Labatt’s general manager, E. M. Burke, found inventive ways to help the company weather Ontario’s Prohibition from 1916-1927. Using the railway and converted military vehicles, Burke managed Labatt’s bootlegging operations, allowing for sale of full-strength beer. For this reason, Labatt’s was one of the few Ontario breweries to survive these years.

A Beer for Women Too

This 1915 calendar encourages women to drink Labatt beers. Women were an untapped market. In the 19th and into the 20th centuries, women who drank alcohol in public invited criticism for their perceived lack of morals. It would take the upheavals of the First World War (1914-1918) to begin to change this attitude.

Appealing to the Working Man

Labatt marketed its beers to unionized workers by informing them that its beers were union made. Labatt workers became part of the International Union of Brewery Workers in 1907.

Brand Appeal

Labatt’s introduced Pilsener beer in 1951. Consumers failed to respond to the European-looking mascot, “Mr. Pilsener,” and it did not sell well. In the late 1960s, the company redesigned the label: it included a Canadian maple leaf, the colour blue, and the beer’s new name, “Labatt’s Blue.” Labatt’s then launched a new advertising campaign that was geared to the youth market. It featured a blue hot air balloon.

Sports Sponsorships

Labatt’s sponsored the Canadian Football League’s Winnipeg Blue Bombers in 1961. The company later sponsored other sporting events, including the Brier Curling Championship. It believed such sponsorships added value by increasing brand recognition.

A Growing Empire

Labatt began to acquire breweries across Canada beginning in the 1950s. This included British Columbia’s Lucky Lager Brewery in 1958 (Lucky Lager), Newfoundland’s Bavarian Brewing Company in 1962 (Jockey Club), and Nova Scotia’s Oland & Sons in 1971 (Schooner). Labatt also opened facilities in Montreal in 1956 and Edmonton in 1977. Labatt had facilities in almost every province in Canada.

A Good Corporate Citizen

Although Labatt’s expanded well beyond southwestern Ontario, it never forgot that London helped it grow. From rescuing Tecumseh Park (now Labatt Park) in 1936 (pictured below), to launching a 24-Hour relay in support of the Children’s Aid Society of London-Middlesex in 1987, Labatt’s has always tried to show the community how thankful it is.

Enter InterBrew

In 1995, Belgian Company InterBrew, makers of Stella Artois, acquired the Labatt Brewing Company, their first international subsidiary. The company had wanted to access the lucrative North American market. The company, which had overextended itself by branching into sports and broadcasting, was ripe for the picking. The Labatt Brewing Company still operates in London.

The McClary

Manufacturing Company

You know the McClary label. It is safer to insist on it. It is your guarantee of quality.

McClary Wireless, 1926

With roots in London dating to 1847, the McClary Manufacturing Company evolved its product line over time. It continued to operate in the city into the 1970s

The McClary Manufacturing Company, as with other early metal working industries in Ontario, benefited from the “tariff of bad roads.” Poor transportation networks made imported goods too expensive for consumers.

At the same time, raw materials were plentiful and inexpensive. Iron ore, for example, came to Canada as ballast on ships carrying the growing numbers of immigrants to the country.

As transportation networks improved in London and beyond, McClary’s grew. It produced a wide range of products for a growing local, regional, national, and international market.

John McClary

In 1852, John McClary joined his brother Oliver’s tinsmith business, launched in 1847. As J. & O. McClary, they soon added a foundry and produced “all kinds of stoves, tinners’ supplies, pressed japanned and spliced wares.” They formed the McClary Manufacturing Company in 1871 and produced stoves, agricultural implements, as well as tin, copper, and pressed metal wares.

Image Left: Photograph, Early 20th Century, Collection of Museum London, 1999

1999.011.190

Introducing Enamelware

In 1880, the McClary Manufacturing Company began to produce a wide range of enamelware. Advertising informed vendors and homemakers that it was practical, pretty, and profitable.

Geographic Expansion

This early 20th century McClary blotter, identifying the locations of the company’s warehouses, illustrates the company’s national reach. It benefited from expanding transportation networks, particularly westward. The company’s products also met the needs of a growing population as immigration to Canada increased in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

McClary Manufacturing Company Factories

The McClary Manufacturing Company’s first factory in London was located at the corner of King and Wellington streets. Demolished in 1955, the factory gave way to Wellington Square Mall in 1962. The company built a second factory on Adelaide Street, just north of the Thames River in 1903. Here, workers manufactured cast iron stoves, furnaces, and other products.

Advertising and Promotion

The McClary Manufacturing Company trumpeted the quality and range of its products. From match holders to ashtrays to toys, their goods reminded customers of the McClary name and reputation.

Tecumseh Ware

In the 1920s, the McClary Manufacturing Company introduced Tecumseh Ware. Company advertising noted this “great Indian ally of the British possessed…staying qualities and loyalty.” Just as “Tecumseh stood behind his pledges, McClary’s stand behind every piece of Tecumseh Ware…” For Non-Indigenous Canadians, Tecumseh was a hero of the War of 1812 and the epitome of the “Noble Savage”: virtuous, brave, and strong. In appropriating his name, McClary’s tried to link their product with these qualities. They also objectified and trivialized this Shawnee warrior and leader.

A Range of Power Sources

In the 1920s, the McClary Manufacturing Company produced stoves that used different sources of power. Some were wood burners, others oil-fueled, and still others electric. While London households had access to the hydroelectric grid from 1910, many rural households were unconnected. They continued to use wood or oil, fuel they could source locally, and which could be transported by rail.

General Steel Wares

In 1927, five Canadian tinware and stove manufacturers, including the McClary Manufacturing Company, merged to form General Steel Wares. An October 1927 Globe and Mail article noted the amalgamation was necessary for the businesses to remain competitive in international markets. General Steel Wares continued to operate in London until the mid-1970s.

Tin Toys

James M. Anderson used his skills as a master tinsmith to make these toy kitchen implements in the late 19th century. His daughter, Mildred, recalled playing with them. A McClary employee, perhaps Anderson scavenged scraps leftover from larger McClary products to make these four small pieces.

1992.031.015A

Women at McClary’s

In this early 1900s photograph, Maude Woodward and Susan Piercey are pictured working at the McClary Manufacturing Company. Women found limited opportunities there. In 1889, John McClary reported that women worked in the tin department where they did soldering and japanning. They worked in a shop separate from the men and earned between $3 and $5 per week. A male tinsmith earned $9.

1982.010.001

War Emergency

These women manufactured munitions at London’s McClary Manufacturing Company during the Second World War (1939-1945). Working class women had worked in factories for decades prior to the war. As a result of the conflict, middle class women joined them. No matter who they were, all women undertook factory work that had been closed to them before the war. They also earned lower wages than men.

Fostering Morale

The McClary Manufacturing Company organized events to build employee morale. This included Christmas parties at which workers’ children received small presents such as this plate. They also included company picnics where workers and their families engaged in different activities such as this tug of war. And they included ceremonies to recognize long service such as banquets for those who worked for the company for 25 years or more. John McClary preferred this form of paternalism over unions, something he vehemently opposed.

Somerville Industries

Limited

Somerville…the name that stands for more than quality…

Somerville began in London as a small paper box making enterprise. It soon grew, diversifying its product line to remain competitive in an evolving market.

In 1886, Charles R. Somerville founded the C. R. Somerville Company to make paper boxes. Starting small with a staff of five young women and one man, the business grew quickly.

Over the decades, the company responded to a changing market by expanding across Canada. Through this expansion, the company also diversified its product line, introducing new materials, designs, and services to stay competitive.

The business operated in London until 1990.

First Customer

To begin, the McCormick’s Manufacturing Company was C. R. Somerville’s only customer. Soon, workers in his factory turned out boxes for milliners, jewellers, druggists, corset makers, hardware merchants, and more.

1990.025.017

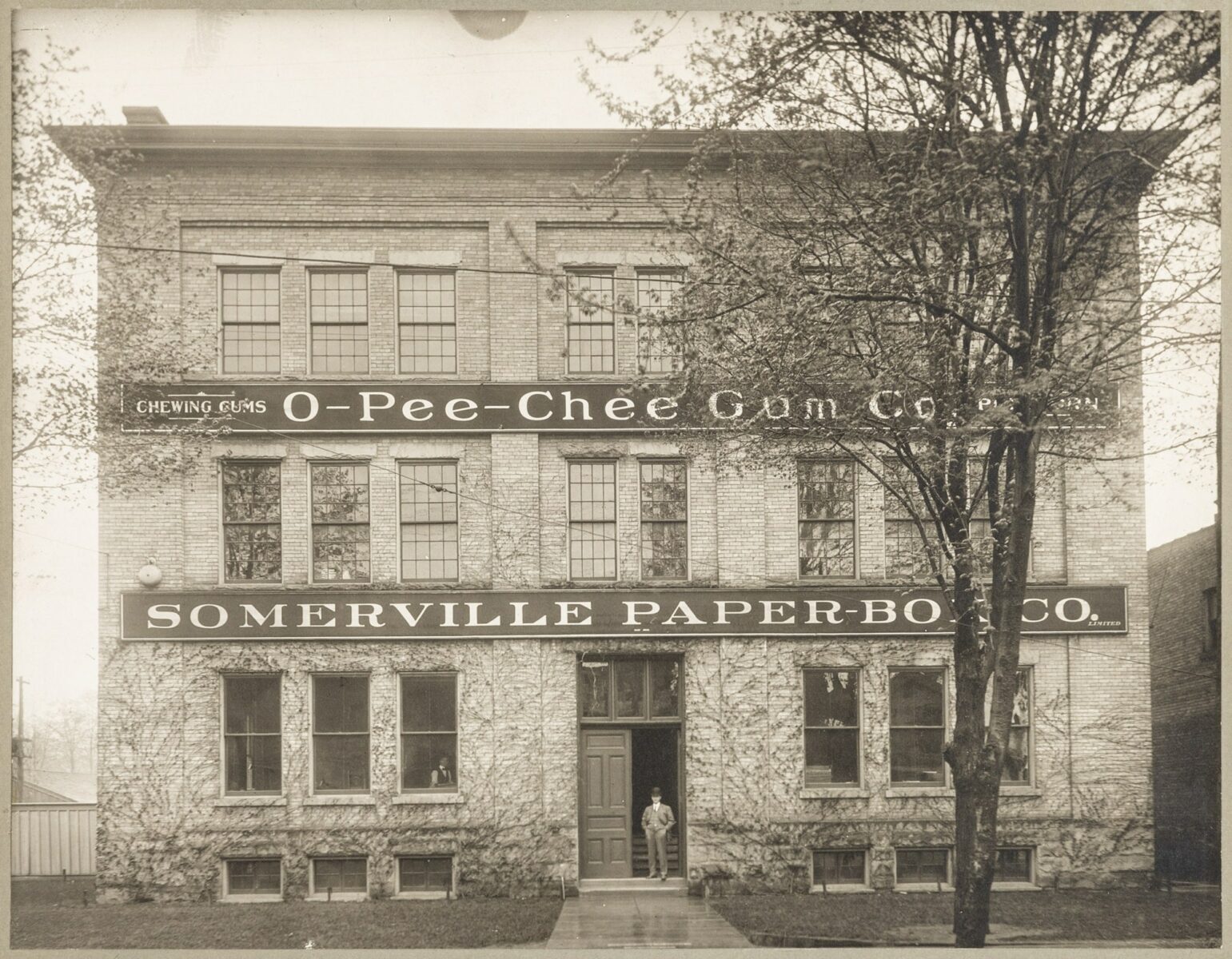

Somerville Paper Box Co.

Here you see the Somerville Paper Box Co. in 1911. By this time, the business had undergone major change. In 1908, C. R. Somerville sold the business to a New York chewing gum manufacturer. Brothers J. K. (1867-1945) and D. H. (1865-1942) McDermid purchased the box-making side of the business from the American firm in 1910. They formed the O-Pee-Chee Gum Company in 1911.

“Lid-Tight” Technology

The underside of the lid of the Perrin’s Famous Biscuits box bears the stamp: “Somerville’s Lid-Tight Patented Feb. 1926.” Its top explains the benefits of the invention: “Notice This caddy will preserve the keeping qualities of the contents equally as well as tins if the cover is kept closed.” Less expensive to manufacture and ship than tin boxes and as effective, innovative packaging like this gave Somerville a competitive edge.

Unipak

London’s Somerville Industries Limited also innovated when it came to packaging beer bottles. Patented in 1957, its Unipak featured a built-in handle, which made the case easy to carry.

Somerville’s Crumlin Plant

In 1946, Somerville Paper Boxes Limited consolidated some of its different facilities into this factory located on London’s Crumlin Side Road. Two years before, in 1944, the McDermid brothers had sold their box-making business to Garfield Weston. This London plant closed on November 30, 1990.

Image Left: Photograph, After 1946, Gift of Somerville Industries Limited, London, Ontario, 1990

1990.025.047

Introducing Puzzles

In 1932, Somerville Limited began making jigsaw puzzles. The market for this pastime had exploded as cash-strapped Canadians looked for inexpensive entertainment during the Great Depression. Somerville also appreciated that puzzle-making kept workers employed in the winter when demand for boxes was low. Fewer layoffs made for a happier, more stable workforce.

Introducing Board Games

In 1934, Somerville signed an agreement to manufacture Milton Bradley games. Somerville was well on the road to becoming Canada’s most diversified toy manufacturer, something it achieved by the 1960s.

The Giant Chink

Somerville manufactured this Chinese checkers game in the 1930s. It is evidence of the longstanding anti-Chinese and anti-Asian racism that pervaded Canadian society in the 19th and 20th centuries. It also illustrates how children internalize racist thinking. Language and imagery in toys express ideology and culture. Toys like the Giant Chink teach children to see difference and belittle those who are different from them. This reinforces the oppression of people of colour.

Women at Somerville Limited

Here, women assemble paper boxes at the Crumlin Plant. The company actively recruited women. One 1947 advertisement read, “GIRLS—here’s work that is clean, light, interesting, pleasant, [and] profitable.” If this drew them, women were told that successful applicants had to be “…alert, intelligent, and dexterous.” Women employed at Somerville also helped manufacture puzzles and games.

1990.025.039J

1990.025.042D

Lawson &

Jones

Established in London in 1882 and part of the city until the early 21st century, Lawson and Jones innovated, diversified, and grew to respond to the markets it served.

Lawson and Jones intend to keep on growing … not in size alone, but in ideas, in service, and in understanding our customer’s needs…

London Free Press, June 11, 1949

In 1882, Frank Lawson, a reporter with the London Advertiser, and Henry Jones, a compositor with the same newspaper, established the printing business that bore their name. At first printing drug labels, the business soon expanded.

A Lawson family enterprise from 1913, the company diversified its product line as well as adopted new technology. This sped up production and improved quality.

Although it expanded its operations across Canada, Lawson & Jones remained committed to London and Londoners. It endured in the city into the early 21st century.

1999.011.130

This photograph depicts the Lawson & Jones production facility in the early 20th century. The signs in the window announce their product line: folding boxes and cartons, advertising calendars, labels and novelties, and envelopes.

Printing Tools

This lithography stone features designs and artwork for some of the many mastheads, receipts, and invoices Lawson & Jones produced. This stone was used in offset printing. First, workers inked the stone. From there, they transferred or offset the images onto a rubber mat and then onto paper. Offset printing is still a popular form of mass-production printing but uses metal plates instead of lithography stones.

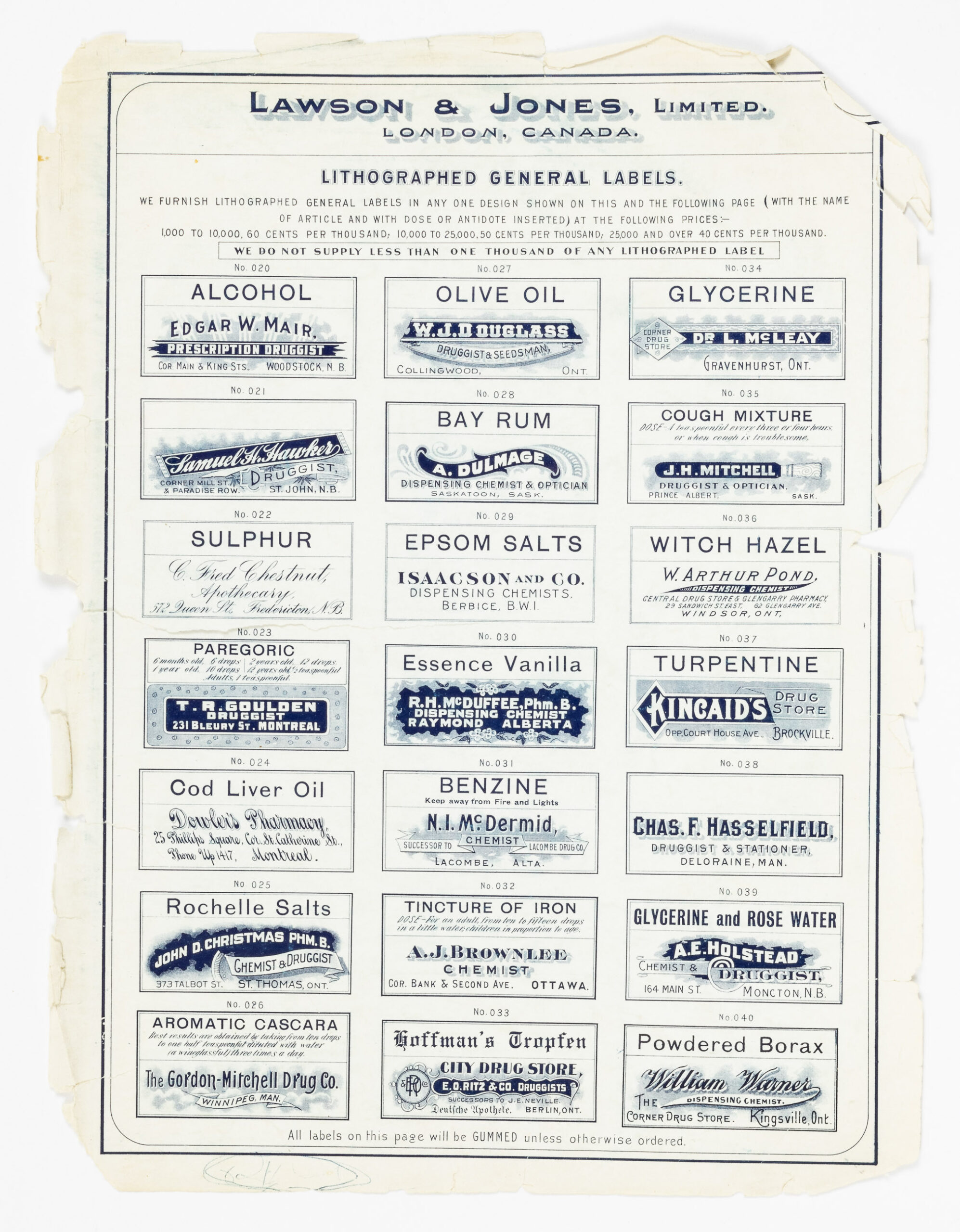

Druggist Labels

In the early 1880s, Lawson & Jones began printing labels for doctors and pharmacists. Frank Lawson had learned that there was no local producer of these labels. Since demand was high, their business flourished. They continued to innovate in the mid-1880s when they began to use pre-gummed paper for these labels. Users no longer had to have a glue pot at the ready.

Passing the Torch

Never strong, Frank Lawson died on October 31, 1911, at only 50-years-old. His son, Ray, a salesman with the company since 1904, became a member of the directorate. By 1913, he arranged to purchase Henry Jones’ shares in the business. Ray Lawson became president of what was still called “Lawson and Jones.”

2004.037.231

Lawson & Jones, Folding Box Department

Lawson & Jones Folding Box Department staff, pictured above, manufactured cigarette box sleeves, among many other products. Company president, Ray Lawson, secured a contract to make cigarette boxes during the First World War. This kept the company afloat. With access to Germany and Great Britain restricted, calendar supplies were cut off. Advertising calendars had been a company staple.

London Printing and Lithographing Company

Lawson & Jones acquired the London Printing and Lithographing Company in 1973. This was one among many companies across Canada and beyond that Lawson & Jones purchased as it worked to stay profitable. The London Printing and Lithographing Company had been established in 1890.

Lawson Mardon Group

Just as Lawson & Jones acquired other businesses, it too became part of a larger business as the stamp on this box suggests. In 1953, Mardon, Son and Hall purchased 50% of Lawson & Jones shares. That grew to 75% in 1976. Changes in ownership did not affect London workers until the early 21st century. Although Tom Lawson fought hard to keep the company in London, the plant closed, and Lawson & Jones left the city.

William Ward

& Sons

Established in 1875, William Ward & Sons cigar manufacturing company endured in London until 1952.

William Ward established his cigar manufacturing firm in 1875. In the early 20th century, this business and its many competitors made London the second largest producer of cigars in Canada after Montreal.

As with other local industries, Ward benefited from London’s rail links. The railway brought in raw materials and carried away finished goods to markets.

Unlike its many competitors, Ward & Sons survived beyond the early 20th century. Weathering both the First World War (1914-1918) and Prohibition (1916-1927), it wound up operations in 1952.

As with his many competitors, William Ward benefited from Prime Minister John A. Macdonald’s 1879 National Policy. This policy placed duties on manufactured products, like German cigars, but not on unprocessed materials like Cuban and American tobacco. As the less expensive option, consumers gravitated to good quality, locally made cigars.

Tools of the Trade

Employees at the William Ward cigar factory once used these tools to make cigars by hand: a tobacco cutter, a rolling board, and a cigar gauge and knife. All that is missing is a pot of tragacanth, or gum, to finish the head of the cigar.

Skilled Craftsman

Here, William Ward employee Richard Swallowell (1890-1953) makes a cigar by hand. At step two of the process, he uses his left hand to handshape the filler leaves that he had already gathered and broken off to the right length. Next, he would have rolled the filler into the binder leaf. Last, Swallowell would have wound the wrapper leaf around the cigar and finished off both ends. It took years to perfect this technique.

Cigar-Making Mould

The de-skilling of cigar-making began with the introduction of cigar moulds like these. The mould did the work of shaping that had once been done by hand. This reduced the training time employees needed and sped up the work. Although men used moulds as well as women, moulds still led to more women in the industry. They had already been employed as wrappers and packers.

Ward Employees

Employees of the Ward Cigar factory pose outside the premises at 64 Dundas Street in this circa 1905 photograph. The industry employed many men. It also had women and children on staff who were far less expensive to employ. Offering further explanation, London cigar manufacturer John Rose noted in 1889, “women do not go on strike and do not get drunk.”

Photograph, Around 1905, Gift of Mr. Robert B. Ward, 1991

1991.019.023

“Dolly Varden”

William Ward issued this poster to encourage customers to purchase its “Dolly Varden” cigars. Dolly was a character in Charles Dickens’ 1841 novel, Barnaby Rudge. Perhaps Ward wished to evoke qualities associated with Dickens’ character: goodness and purity. Perhaps he was copying a fad. Everything from a dress to a dry goods store to a fish species was named after Dolly Varden.

Sir Douglas Haig Cigars

As an expression of patriotism during the First World War (1914-1918), William Ward named a cigar for Sir Douglas Haig. In 1915, Haig became the commander of the British Expeditionary Force, which included the Canadians.

Conferring Sophistication?

William Ward and his many London competitors enjoyed a robust market for cigars in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Less expensive to manufacture, cigars also became less expensive to purchase. No longer the preserve of the upper classes, men of more modest means picked up the habit. For many, cigar smoking suggested sophistication and conferred status and prestige.

Racist Packaging

The graphics on cigar boxes featured fictional characters, historic figures, and drawings of plants and animals. Some also featured racist depictions of Japanese, Arab, and Indigenous peoples, among others. All active, vibrant members of Canadian society at the time John McNee & Sons, George E. Patrick, and the London Cigar Company, respectively, released these cigar boxes in the late 1800s through to the early 1900s, the imagery on the boxes depicted them as foreign and exotic “others.” This aligned with and reinforced the stereotypes and racist ideas that permeated Canadians’ attitudes towards Japanese, Arab, and Indigenous peoples.

Prohibition and Cigars’ Decline

When the Ontario government introduced Prohibition in 1916, cigar manufacturers suffered. Taverns had been a major site of cigar sales.

Cigarettes and Cigars’ Decline

This is a 1914 Princess Mary Gift Box. Those that officers and men received contained a pipe, a lighter, an ounce of tobacco, and twenty cigarettes. Cigarettes also formed part of soldiers’ weekly rations. When soldiers returned home, they continued to smoke cigarettes instead of cigars. By this time, cigarettes suggested male sociability, modernity, and middle-class respectability.