For Sir John Graves Simcoe, part of the appeal of the forks of the Thames in 1793 was its distance from the United States, a potential enemy.

About four decades later, London became Western Canada’s military headquarters following the Upper Canada Rebellion (1837-1838). The presence of the military jumpstarted London’s growth.

In the 20th century, Canada’s conflicts overseas galvanized Londoners. In both world wars, they enlisted in Canada’s military. They worked in their city’s factories. They volunteered their time. And they gave their money.

Explore the conflicts that impacted London and Londoners…

1837 – 1838

Upper Canada

Rebellion

1866 – 1871

Fenian Raids

1885

Northwest Resistance

1899 – 1902

South African War

1914 – 1918

First World War

1939 – 1945

Second World War

1837 – 1838

Upper Canada

Rebellion

“We lived in hourly apprehension of invasion…”

Verschoyle Cronyn, reminiscences, 1911

“London was so thickly beset with disaffected Americans during the rebellion, that it was deemed necessary…to station this force in the heart of the district…”

Sir Richard Henry Bonnycastle, Canada and the Canadians, 1849

The 1837 Upper Canada Rebellion played a significant role in shaping London’s future.

In December 1837, rebels in Upper Canada hoped to overthrow the Upper Canadian political and religious establishment. They wanted a say in the province’s political affairs.

British forces quickly dispersed the rebels and their leaders fled to the United States. From there, they staged raids into the Western District.

In response to the rebellion and to quash border raids, the British military established new garrisons, including one at London. Serving the varied needs of this garrison led to the community’s growth.

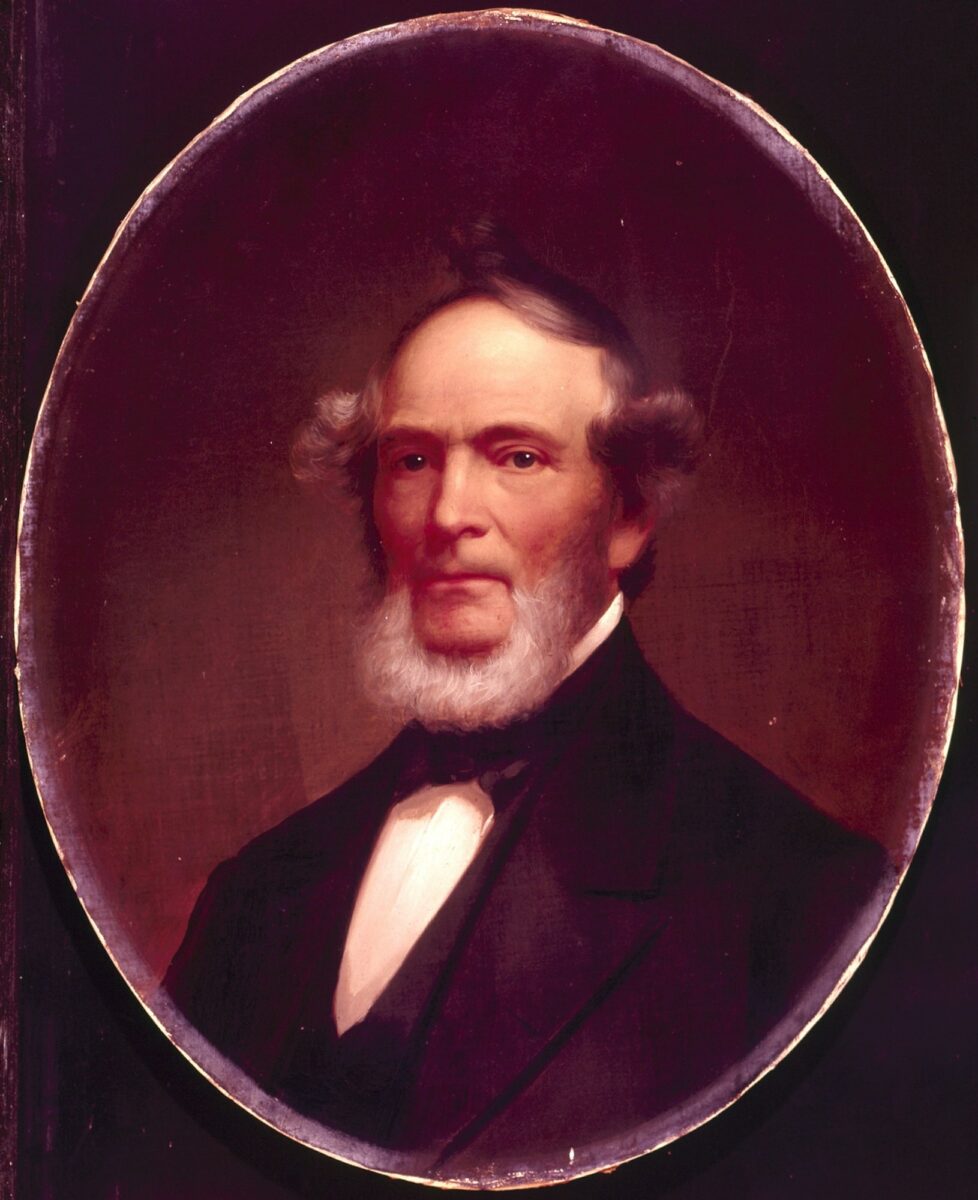

Rebel Leader

In December 1837, Dr. Charles Duncombe led the Upper Canadian rebellion in the London District. Learning of William Lyon Mackenzie’s uprising in Toronto, Duncombe gathered several hundred supporters to stage a rebellion further west. Hearing of Mackenzie’s failure and the amassing of an opposing force, Duncombe and his men fled.

Lt-Col. Maitland’s Coffin Plate

This shield decorated Lieutenant-Colonel John Maitland’s coffin during his January 1839 funeral in London. Londoners lined the streets to watch the procession. A year earlier, they had watched as Maitland and his 32nd Regiment marched into the village to establish a garrison. These forces quashed cross border raids in the Western District that Charles Duncombe and others organized from the United States.

The London Garrison

Dennis O’Brien’s red brick building stands to the left of the crenellated courthouse in George Russell Dartnell’s 1841 watercolour. When the British garrison arrived, military officers lived in there until barracks could be built. For their part, the men lived in tents. The military paid cash to local builders to construct the new barracks. It also paid local businesses cash for food, beer, and leather goods. This helped end the economic hardship the rebellion had caused. It also promoted London’s growth as new entrepreneurs arrived. Except for the period 1854-1862, the military stayed until 1869.

The Gaol and Courthouse, London, Canada West, c. 1841 (Reproduction)

watercolour

Art Fund, 1948

Royal Welsh Fusiliers

Lieutenant Thomas Parker Rickford (1820-1869), of the 23rd (Royal Welsh Fusiliers) Regiment of Foot, stored some of his belongings in this box. He was with the regiment when it was stationed in London in the mid-1840s. The regiment returned for the years 1850 to 1853.

Punishing the Rebels

The cell ventilation grate formed part of the new London jail completed in 1846. The original jail was too small, leading to terrible overcrowding in the wake of the Upper Canada Rebellion (1837-1838). Justice was harsh, too. Six rebels were hanged after a failed attack at Windsor on December 27, 1838.

1866 – 1871

The Fenian Raids

Warn your company to be ready to turn out at a moment’s notice.

Telegram from Lieutenant-Colonel John B. Taylor to Captain John C. Frank, 1868

Between 1866 and 1871, the American-based Fenian Brotherhood hoped to secure Ireland’s independence from Britain by capturing Canada.

In 1865, Britian crushed the Irish independence movement. In response, membership grew in the Fenian Brotherhood, a secret society that included many Irish American Civil War veterans.

They hoped to bring about Irish independence by staging cross-border raids into Canada. From 1866 through to 1871, British and Canadian officials monitored Fenian activity, deploying military forces to Sarnia, Windsor, and other locations to engage them.

The Fenians defeated a small Canadian force at the Battle of Ridgeway in June 1866. Their other raids failed.

Click on the objects to learn more…

A Fenian Raid Veteran

In 1899, Gunner J. Law of the London Field Battery applied to receive this Fenian Raid service medal. To be eligible, he had to have been on active service in the field, detailed for a specific duty, or have guarded a location where a raid was anticipated.

1958.001.205

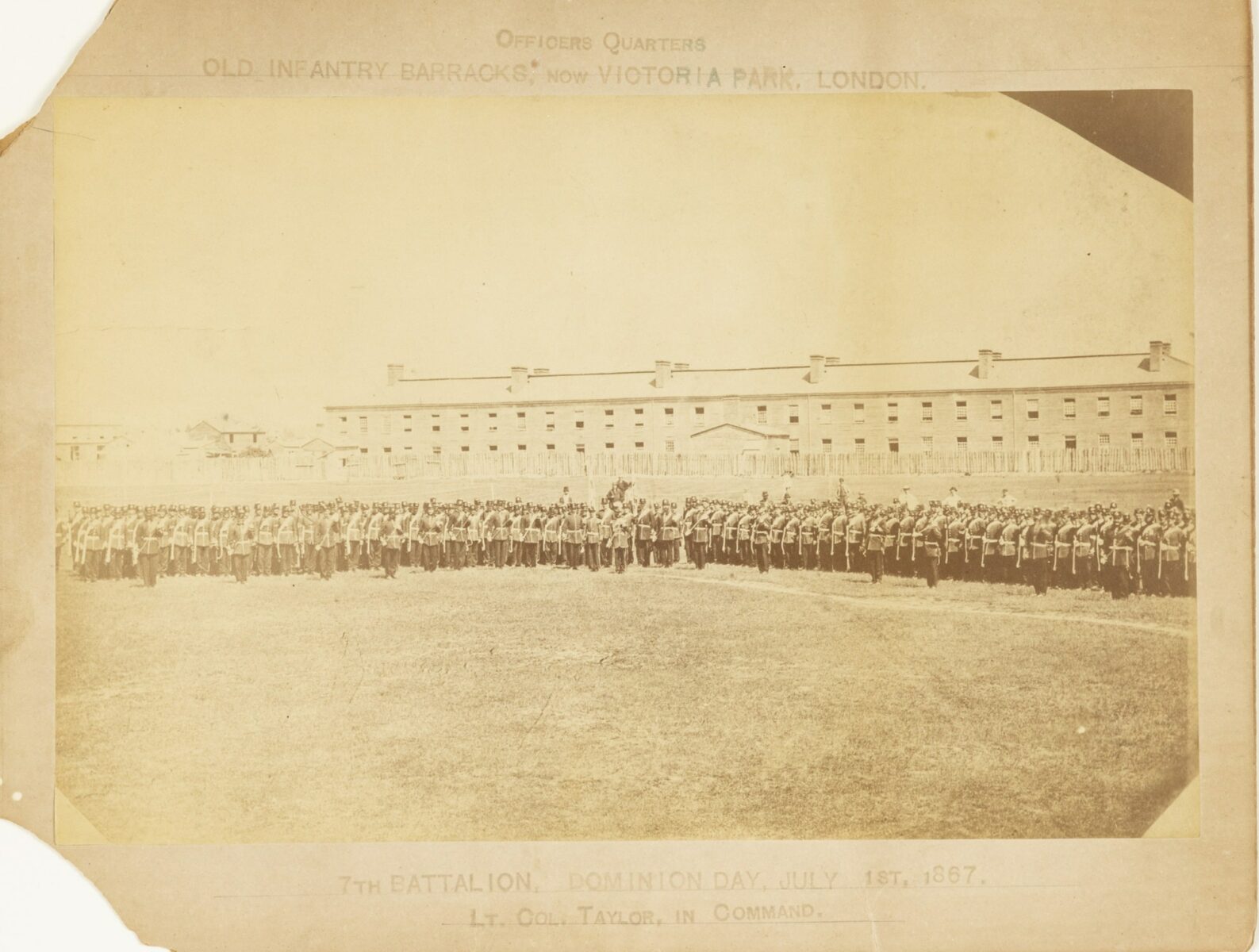

A Spur to Confederation

Above London’s 7th Battalion, London Light Infantry, pose on the first Dominion Day, July 1, 1867. The Fenian Raids helped bring about Canadian Confederation in 1867. The individual provinces recognized their vulnerability to attack. They also recognized the United States’ military and economic strength.

1885

Northwest Resistance

In 1885, London’s 7th Battalion Fusiliers left London for the long journey to join government forces in the Northwest. They arrived after the conflict ended.

Louis Riel led Indigenous fighters in a series of battles against government forces in 1885.

First Nations and Métis fought to protect their rights, land, and ways of life against government encroachment. For its part, the government fought to solidify its hold on the land and to demonstrate military capacity to land-hungry Americans.

After a series of battles, Riel’s forces lost at Batoche in May 1885.

Click on the objects to learn more…

1999.011.106

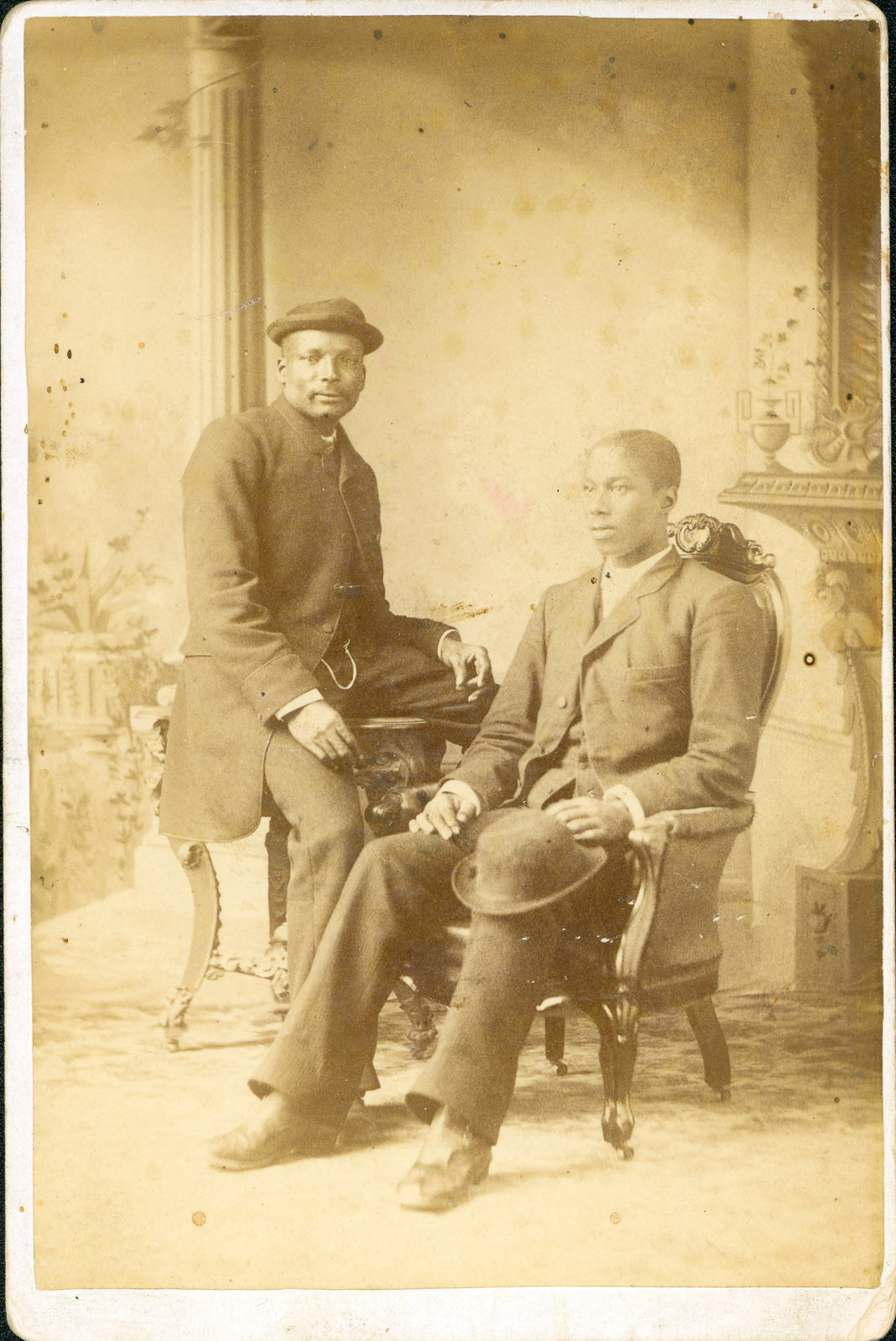

Home from the Northwest

Here you see the 7th Battalion Fusiliers home from their participation in the Northwest Resistance. Mobilized on April 1, 1885, they returned to London in July without having fired a shot in battle.

1899 – 1902

South African War

The platform from end to end was packed…

London Free Press, October 26, 1899

Between 1899 and 1902, Londoners were among the 7000 Canadians to fight in Britain’s South African War.

As with many English Canadians, patriotic zeal fired Londoners when Great Britain’s war with the Boer Republic began in October 1899. They believed that Great Britain was fighting a war to bring British civilization to a backward people.

Many of the young men who enlisted believed it was their duty to support the Mother Country. Many also hoped for adventure and an escape from humdrum lives.

On the home front, Londoners supported the troops, harnessed economic opportunities the war presented, and mourned their dead.

To South Africa

Here volunteers leave London on October 25, 1899, to fight in Great Britain’s South African War (1899-1902). Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier (1841-1919) addressed them before they left. He complimented the men on their loyalty to the flag and urged them to do their duty.

Click on the objects to learn more…

1914 – 1918

First World War

Wild cheers went up when the declaration of war was announced…

London Free Press, August 5, 1914

The men, women, and children of London participated in the First World War in a wide variety of ways.

When Great Britain declared war on Germany on August 4, 1914, Canada was at war. London’s men, women and children participated overseas and at home.

Thousands of men and women enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

At home, men and women worked in industry and on farms to supply munitions and food. Adults and children alike raised money and made comforts for those overseas.

From the war’s end on November 11, 1918, until today, Londoners remember the war and those who served.

2002.022.141

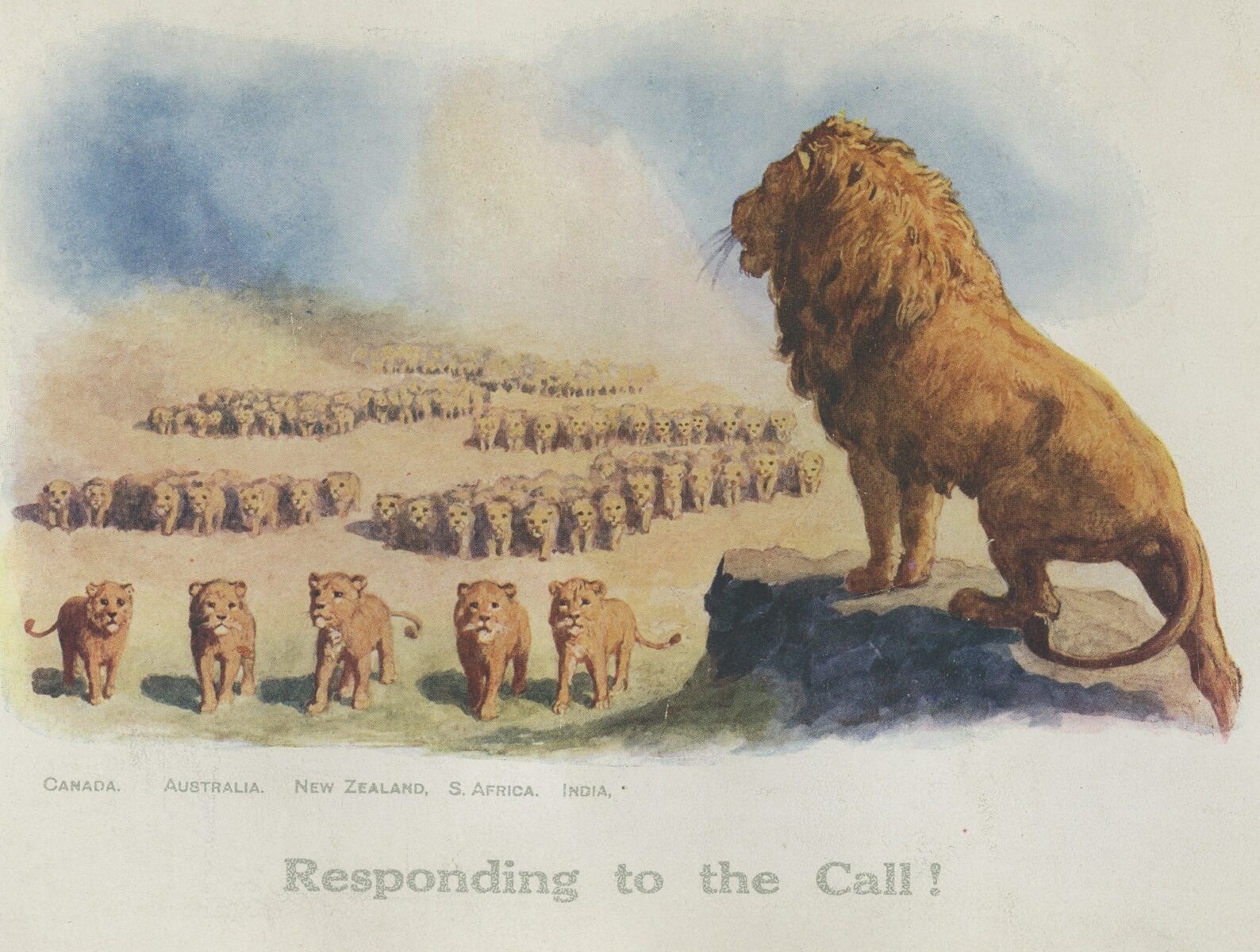

“Responding to the Call”

In this patriotic drawing, Great Britain, represented by the adult lion, summons the countries of its Empire, including Canada, to join its war effort. Britain had declared war on August 4, 1914. Part of the British Empire, Canada was immediately at war, too. Britain had declared war because Germany had reneged on an 1839 treaty to respect Belgian neutrality when it invaded that country in August 1914.

1978.044.063

Signing up Londoners

In the 1914 panoramic photograph above, men of the 18th “Western Ontario” Battalion stand on the grounds of Wolseley Barracks, Carling Heights. The battalion was authorized on November 7, 1914. In late 1915, the 142nd Battalion, “London’s Own,” began recruiting in the city. It was the only unit composed entirely of Londoners.

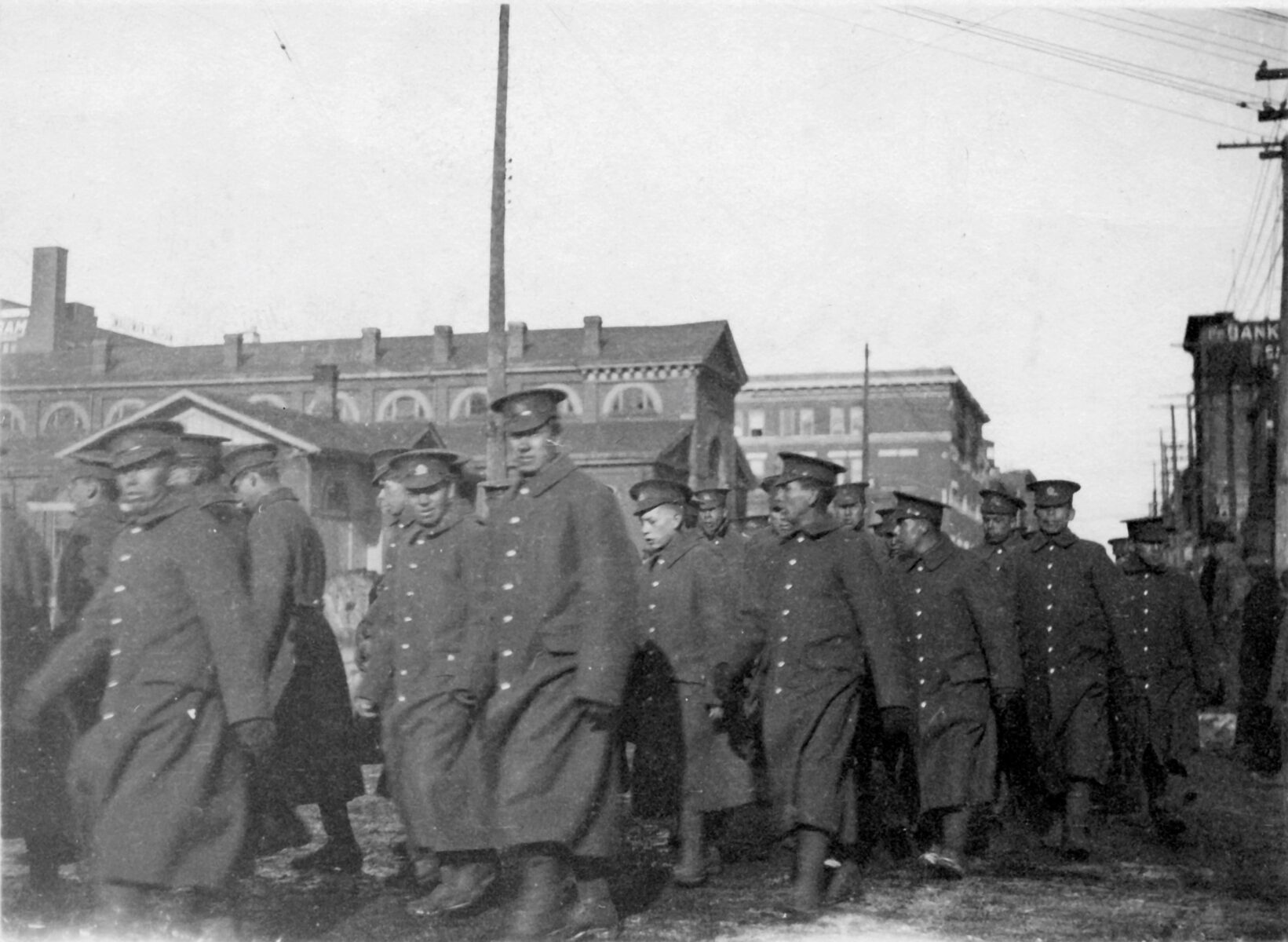

First Nations Recruits

These men from Moraviantown joined the 33rd Battalion in London in 1914. They were among the almost 4,000 men of Indigenous ancestry in Canada to enlist. Many encountered racial prejudice at first but later gained acceptance. They proved to be skilled and effective soldiers and officers. At least 50 earned decorations for bravery.

African Canadians in the CEF

Here, one African Canadian soldier sits among his white counterparts. When war broke out, many Black Canadians wanted to enlist. The majority found that racist attitudes blocked their admission. They continued to lobby and in July 1916 the No. 2 Construction Battalion was established in Nova Scotia. More than 6000 Black Canadians from across the country enlisted, including this man.

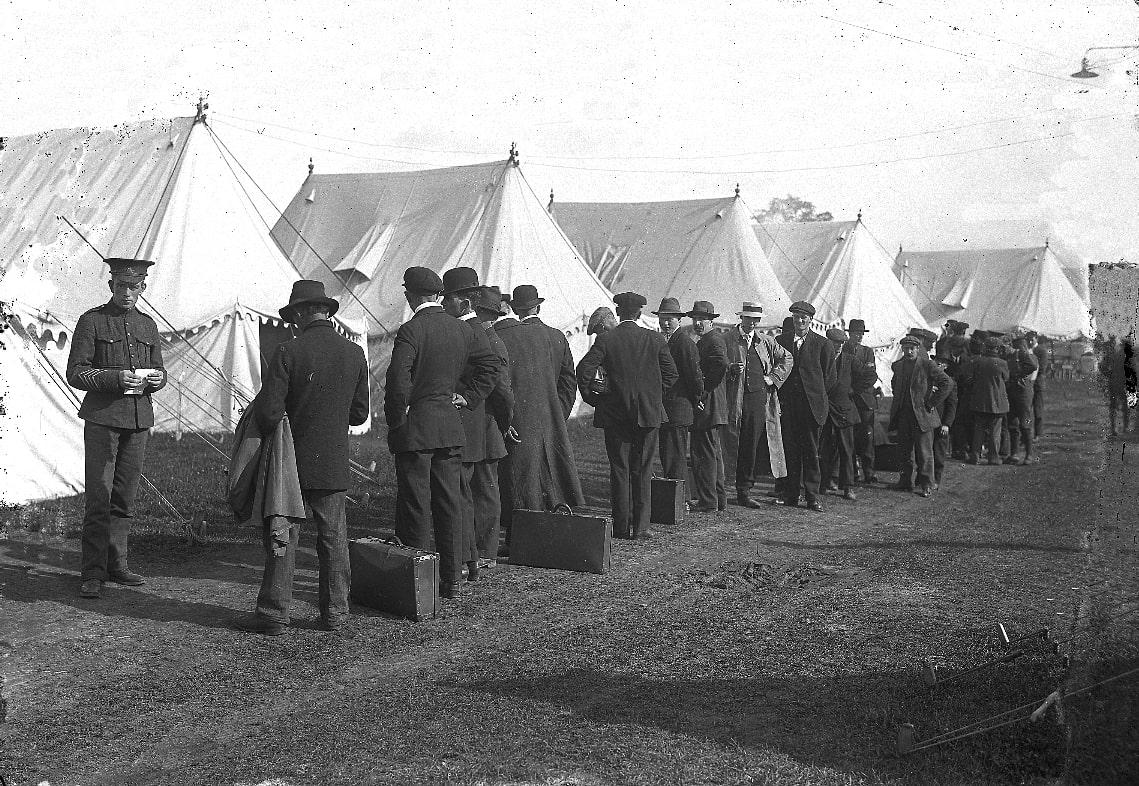

Training New Recruits

Here, new recruits line up at the training camp at London’s Carling Heights in 1915. In 1914, training in Canada happened at Valcartier Camp. Later, the government decentralized training. London welcomed thousands of new recruits who had to be trained to follow orders and to use different weapons. Londoners found the influx difficult but developed services to amuse the soldiers.

Rest and Relaxation

These soldiers relax at London’s Morkin Hotel (right) and in the smoking room of the Soldiers’ Club established by the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (below). As business owners, charitable workers, and private citizens, Londoners tried to make the thousands of soldiers who flooded the city comfortable.

Victory Loan 1918

This 1918 subscriber card and pin feature the Victory Loan honour flag. When London received its flag, it also featured a crown. It told all who saw it that Londoners had subscribed 25% above their quota. London had raised $9, 087,100 instead of $7,300,000. The 1918 war bond drive was the fourth the Canadian government launched to pay its war debt.

“A Help to Victory…”

London’s Louise Wyatt received these certificates in 1916 and 1917 for buying war savings stamps. She was one of thousands of children across Canada who supported Canada’s war effort in this way.

Comforts for the Troops

The volunteer work of the men and women of London and the surrounding region was crucial to Canada’s war effort. They knit socks and sweaters and sewed bandages and pajamas, among hundreds of other items. These things not only looked after the soldiers physically but emotionally, too. They were concrete evidence that their loved ones had not forgotten them.

1999.011.266

Prohibition

This is a pre-First World War pro-Temperance button. Its owner would have been satisfied when the federal government enacted prohibition in 1917. This measure was intended to prevent waste, maximize efficiency, and preserve grain resources by banning the manufacture, import and sale of alcohol. Prohibition was repealed shortly after the war.

Click on the objects to learn more…

2001.026.003

Dr. Edwin Seaborn (1872-1951)

In 1916, Dr. Seaborn received command of the No. 10 “University of Western Ontario” Stationary Hospital. By December 1917, the unit operated a 400-bed hospital in Calais, France. By the end of the war, the No. 10 Canadian Stationary Hospital had cared for over 16,000 patients.

Following Seaborn’s 1951 death, his wife Ina, received the Memorial Cross. Although he had lived a full life, Seaborn’s war service contributed to his death.

Nursing Sisters

Londoner Agnes Balfour Davis (b. 1875) received these medals for her service as one of Canada’s more than 3,000 Nursing Sisters. Davis enlisted in September 1914 and was among the 2,504 who served overseas. She returned to Canada in 1916, suffering from the stress of work. She was lucky. Fifty-three of her nursing sister colleagues died from wounds, disease, or drowning.

Click on the objects to learn more…

1939 – 1945

Second

World War

Canada at War with Nazis; House Almost Unanimous

London Free Press, September 11, 1939

From 1939 to 1945, Londoners were part of a Total War that drew men and women into the military and mobilized all the community’s resources.

Canada declared war on Germany on September 10, 1939, seven days after Great Britain. The following six years saw thousands of London’s young men and women enlist in the various branches of the Canadian military.

At home, men and women worked in industry and on farms to supply munitions and food. Adults and children alike raised money and made comforts for those overseas.

From the war’s end in Europe in May 1945 and in the Pacific in August 1945, until today, Londoners remember the war and those who served.

Showing Support

Londoners wore pins to welcome King George VI (1895-1952) and Queen Elizabeth (1900-2002) on their visit to London on June 7, 1939, a stop on their Canadian tour (May 17 to June 15). Left, they are pictured greeting some of London’s First World War veterans. It was the first time a reigning monarch had visited Canada. Londoners, as with other Canadians, recognized the purpose of the visit: to muster support for England in the event of war.

Click on the objects to learn more…

Serving in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF)

Gordon Russell Elliot joined the RCAF with the hope of becoming a pilot, but his medical examination revealed that he was colour blind and therefore could not distinguish the various lights on the instrumentation panel. He switched to navigation but a crash-landing during training prompted him to transfer to the dispatch rider section of the army. He was on the train to Halifax when peace was declared.

In the RCNVR

Londoner Lieutenant James Shuttleworth wore this Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve service cap. He served on a frigate in the North Atlantic during the Battle of the Atlantic, helping to protect vessels from German submarine attacks. Those vessels carried crucial military supplies and personnel from Canada to the United Kingdom.

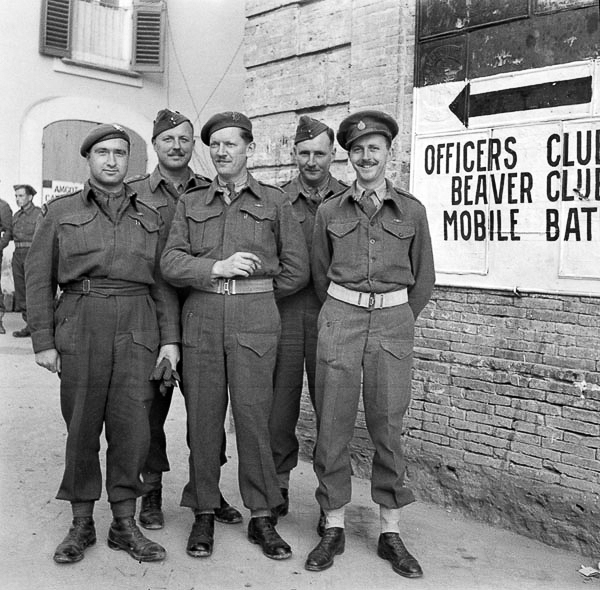

Londoners in Italy

From left to right, Londoners Captain Sam Lerner, Captain R. B. Watson, Major M. H. Hodgins, Captain J. A. Johnston, and Captain J. L. Morrison pose in San Vito Chietino, Italy, in 1944. They were among the more than 93,000 Canadians who fought in the Italian Campaign.

Liberating the Netherlands

Londoner Irene Brown (1893-1978) received the Dutch wooden clog from M. K. Roblin. It is engraved “M.K.R. Holland ’45.” Perhaps Roblin was part of the First Canadian Army. From September 1944 to April 1945, Canadians fought German forces in the Netherlands. They opened the country to food and other aid as they cleared out the German forces.

Women’s Services

Some 22,000 Canadian women served in the Canadian Women’s Army Corps between 1941 and 1946. As with the Royal Canadian Navy and the Royal Canadian Air Force, the army recruited women to free men for combat roles. They worked as cooks, drivers, and office workers, among other tasks. In London, Helen Brownlee was the first woman to enlist with the CWAC.

With the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN)

Lorne Benner (b. 1924) served as a signaller on HMCS Stormont from 1943 until 1945. This River-class frigate escorted convoys during the Battle of the Atlantic. It also supported the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944.

War is Over

The Honourable Ray Lawson, Ontario’s Lieutenant-Governor, received this commemorative trowel. He had laid the cornerstone of a new wing to London’s Children’s War Memorial Hospital on October 26, 1949. At the end of the First World War, Londoners chose to build the hospital to remember their war dead and honour those who fought. Londoners chose the same path at the end of the Second World War. The war in Europe had ended on May 8 and the war in the Pacific on August 15, 1945.